Banner Photo: Sarote Impheng Sripfoto

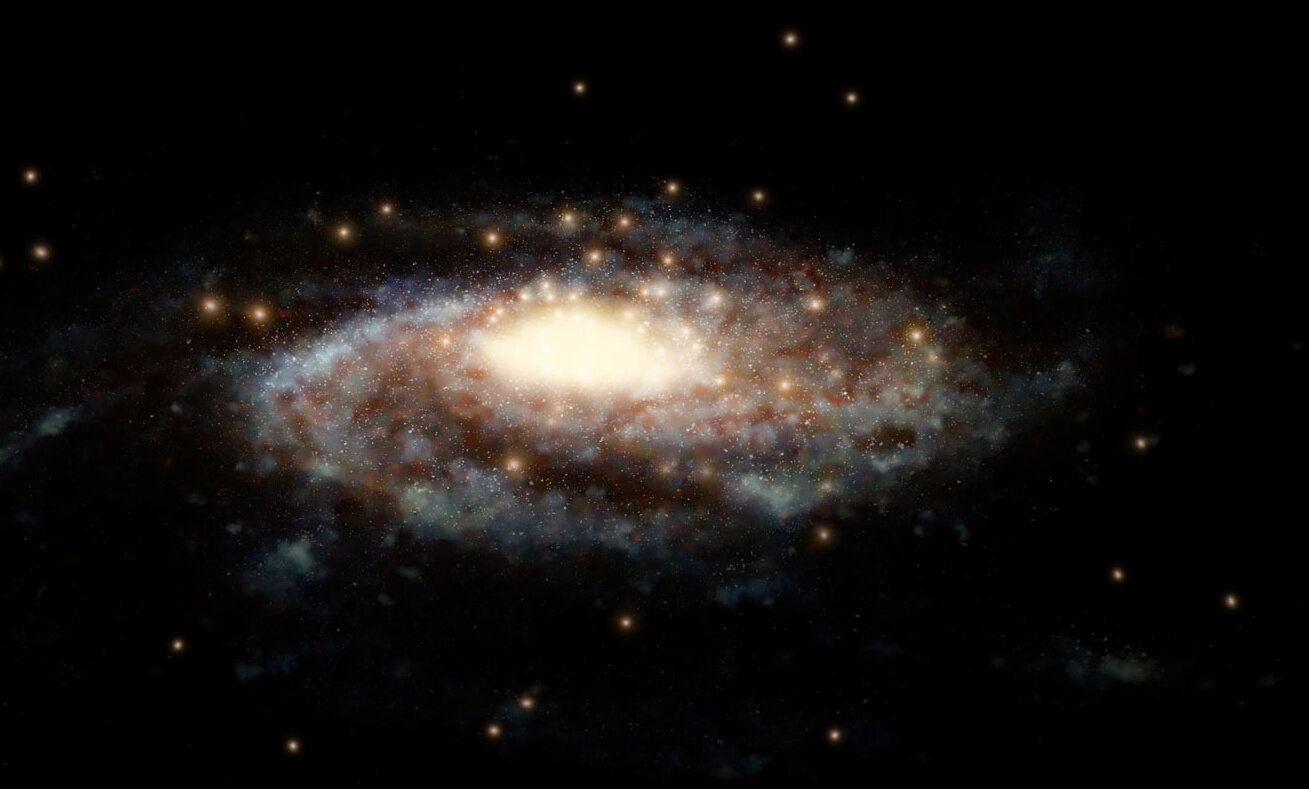

In September 2018 I made my first visit to Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO), perched on a craggy outcrop of the San Gabriel Mountains a mile above Pasadena, California. At the observatory between 1914 and 1919 my grandfather Harlow Shapley discovered the true shape of Milky Way galaxy and our place in it.

Aerial view of Mount Wilson Observatory. San Gabriel Mountains National Monument, California. QT Luong/terragalleria

Shapley found the galactic center was a dense region far, far away from our sun and planets. In fourteen “magisterial” papers published from 1917-1919 he overthrew the long-held belief that our Sun was the center of the Milky Way galaxy, which was believed since ancient times to be the entire universe.

His conclusions were wrong on some counts. But his methods and stunning main result using the 60-inch telescope, then the most advanced in the world, helped make the MWO “where we discovered our place in the Universe,” as its website says.

Background:

It may be surprising that this was my first visit to a working observatory. But I and the other grandchildren of Harlow and Martha Betz Shapley were not under pressure to learn astronomy. On the other hand, their five children grew up in the official Residence of the Director of Harvard College Observatory. Shapley became its Director on December 1, 1921 at age 36; he moved in to the Residence with his young wife Martha and their three children; two more were born there. Eldest son Willis as a youth gave tours of the observatory to visitors. Number two son Alan had a job at the HCO Oak Ridge Observatory in rural Massachusetts repointing the telescopes and cameras through the night. But my experience was limited to one climb into the old chair of the 15-inch Great Refractor at HCO in daytime.

MWO noted the centennial of Shapley’s great discovery with this graphic. T-shirts are now sold out. © MWI

Pasadenans looking at the ridgeline of the mountain can discern the white towers of tMWO’s 150-foot and 60-foot solar observatories. Online, the HPWren TowerCam offers people a continuous view of the campus, cloud and sky conditions.1

The MWO’s fame extends way beyond Pasadena. George Ellery Hale the wealthy astronomical entrepreneur chose this peak for its remarkably clear and stable air. There Hale built a series of remarkable instruments, helped by Andrew Carnegie’s money.2 The first advanced Hale’s passion to understand the internal physics of the sun and other stars. The solar towers enabled Hale to confirm the Sun’s magnetism, for example. Next up was an optical telescope with a world-beating 60-inch mirror; its first image was taken December 24, 1908.

The dynamic, driven Hale was not satisfied. He started a second telescope based on the first but with a 100-inch mirror. The 100-inch telescope (sometimes called the Hooker for the donor) saw first light in November 1917. On that instrument between 1923 and 1929 Edwin P. Hubble confirmed the universe had millions of galaxies beyond ours. They were also mysteriously flying away, as shown definitively by Hubble and then by Hubble and Milton Humason.

Today active research on the mountain is done by the newer six telescope CHARA Array and other installations; but the big attraction remains these early Hale-built instruments that propelled one of the most dynamic epochs in the history of science.

Mules hauling parts for the 60-inch up mountain.

Photo: The Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif.

Robert Anderson was a great guide. He worked for the Mount Wilson Institute, which manages the observatory for the Carnegie Institution for Science. For starters, Robert drove nimbly the 44 miles of ascending road from Pasadena. The last stretch is Red Box Road, that twists along the cliff edge. Today’s ascent is luxurious compared to the labors of mule-drawn wagons that hauled 150 tons of parts to the 60” telescope to the summit between 1904 and 1908

We came for a Public Ticket Night when people can look through the 60-inch telescope. Near sunset we strolled on the simple walks, past the towers of solar observatory and the big dome of the 100-inch optical telescope. Among the pines is a small museum. Also a refreshment area called - what else - Cosmic Café.

The path led us to a plain door in the 60-inch telescope’s dome. I stepped across the threshold into a dim space, with a wall that encircled the pivot and supports for the massive telescope overhead. I seem to have time-traveled into the Age of Iron when the parts of the behemoth hauled up the road had been assembled. The enormous gears lying around looked big enough to drive the Titanic.

The engineering had been precise.3 Two-ton gears were etched with 1,080 teeth to move the telescope to compensate for the earth’s rotation. The entire dome rotates on rail car-like wheels double-smoothly. This and other facts are in Building the 60” Telescope by Mike Simmons on the MWO website. The big old parts are kept to show the craft involved making “one of the most successful and productive telescopes in history.” It has been in use almost every clear night for 85 years, Simmons wrote.

Robert and I climbed narrow stairs into the huge dome, 58 feet across and at least as high. The huge telescope tube was pointed at yet another world, the bluing slit of sky visible where the massive shutters had been pulled back. In the darkening sky, we saw flecks of light.

Public Viewing Night at 60-inch Telescope. Author photo

About two dozen ticket-holders were there. Some were astronomy buffs talking shop; others like me just took in the scene. A modern touch was a gleaming laptop screen on a side table. It was programmed with images and data for each celestial “object: we would see. Small wonder that today we can see objects millions light years away anytime via the Internet. But admit it: The Mona Lisa doesn’t look so great on a laptop. Tonight our viewing would be in the astronomic equal of the Louvre, seeing of authentic works of art.

Each time that evening, to show us another slit of sky, the great telescope was pointed to its zenith - six o’clock - so the dome could be rotated and the shutters opened in the next position. Dooley wheeled a set of steps next to the base of the tube. He climbed and adjusted the eyepiece about 15 feet above the floor. Then we took turns climbing the steps, leaning out to the little eyepiece for a view. It was like mounting a fat horse: weight on left foot, swing the right leg over, then lift. Close one eye; squint with the other.

Saturn’s bright sharp rings leapt at me through the lens. Then the machinery was moved so we could view a spiral galaxy. Its dainty whirling veils were as alluring as in Shapley’s day, when they were little-known “nebulae.” Again telescope moved to six-o’clock and the dome rolled. Now the slit of sky could show us a globular cluster.

It seemed a set of jewels beautifully arranged like an old-fashioned brooch.

Was it winking at me? No. Only my eye pressed against the eyepiece had blinked.

A century before, Shapley used 300 images taken with this great apparatus to study globular clusters, in ways not possible before. He counted 69 clusters; many seemed farther than any measured before. So he devised yardsticks based on the Period-Luminosity law which Henrietta Swan Leavitt had published in 1912 to find distances to Cepheid variable stars in the Magellanic Clouds, in the southern hemisphere, which are closer to us.4

When Shapley mapped the globular clusters, they showed “peculiar asymmetry,” he wrote later. In that moment he realized, “Good Heavens! It means the center of the universe may be way off in the Sagittarius direction.”

“I should not say nor think that the center of our universe is so remote and removed from us…the proud observers. No, I should say that the trivial observer is far from the magnificent, star-filled center! He is the peripheral, the ephemeral one.”5

***

Observation was hard work. The astronomer was ensconced on a moveable platform attached to the rim of the dome. He could drive the platform in three dimensions, like a modern lift, while controlling both the dome rotation and the telescope angle. The 60-inch enabled him to make photographs at two focal lengths; one was near the top of the telescope, so he raised the platform to settle in perhaps 40 feet above the floor. The dome’s vast interior was dark and cold.

To make an exposure (or photograph) he had to locate his target on the focal plane of the eyepiece. He adjusted the small glass plate in its adjustable tray. When the image looked just right, he uncovered the glass. Instantly, light that took tens of thousands of years to reach the telescope began to etch his plate.

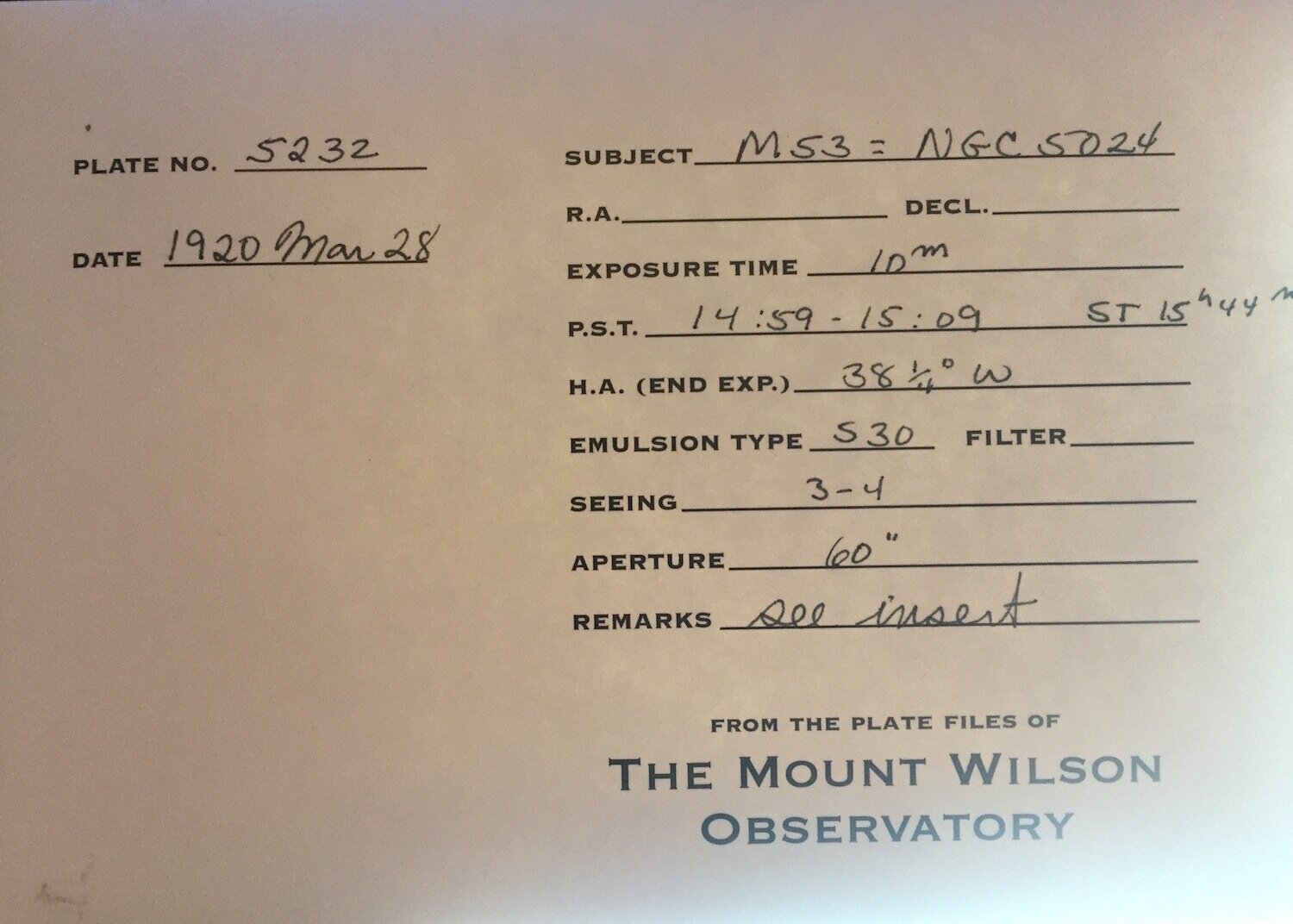

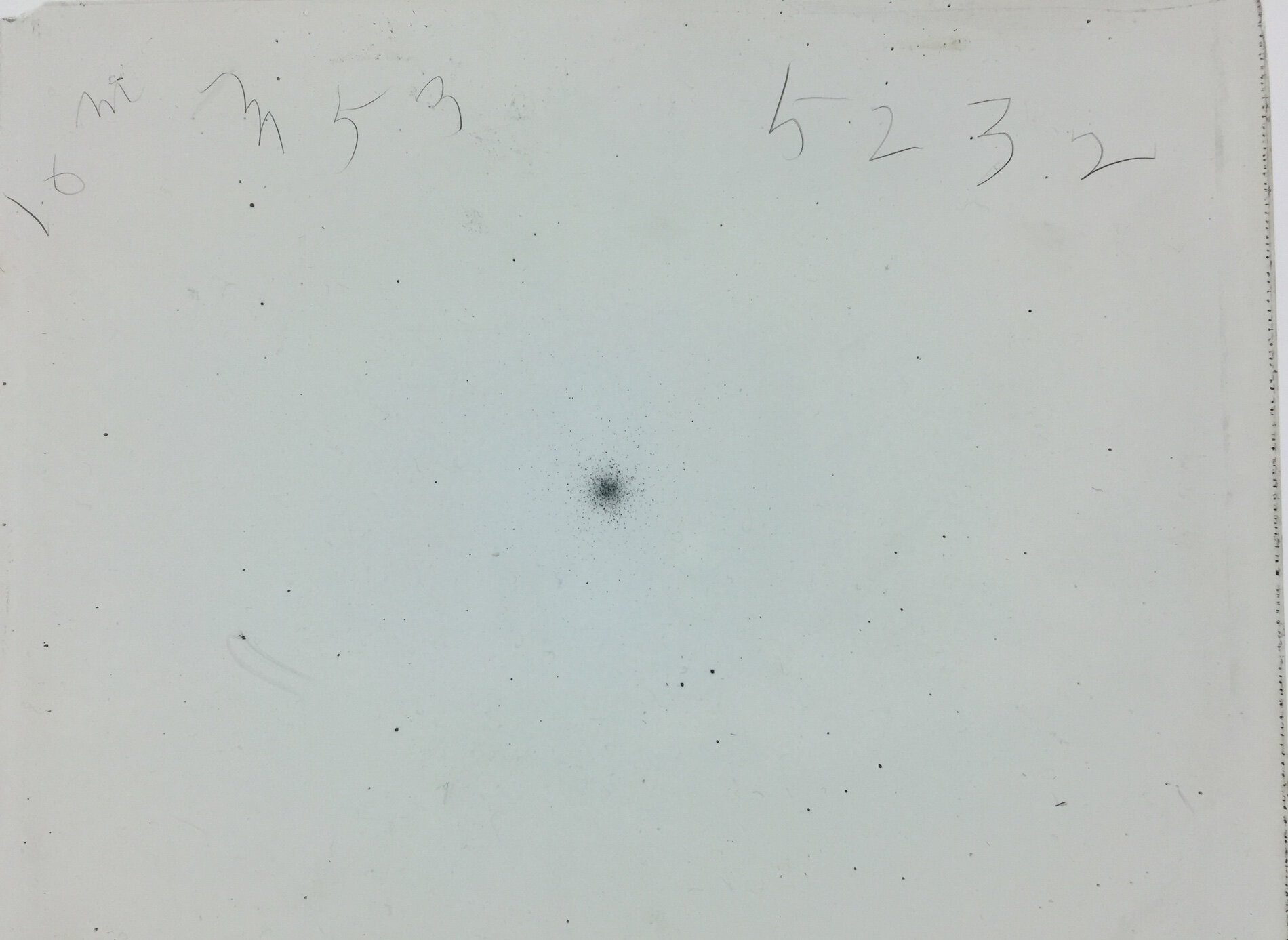

He had to keep the image focused as long as needed. With a clear sky, a good exposure could be had in minutes. Some nights he needed to watch his plate for hours to collect enough light. The globular cluster M 53 that Shapley photographed March 28 1920 required ten minutes, for example.

The MWO working environment was run by Walter Adams, a noted scientist and strict Yankee. Adams was acting MWO director during World War One because Hale, the Director, was mostly in Washington advising the government.

Just four nights per month are moonless enough for stellar photography, so astronomers competed for “run time” on the mountain. The astronomer had to plan “excruciatingly well for a … run,” writes Allan Sandage in his history of the observatory.6 The astronomer’s assigned night assistant was invaluable. These were dedicated mechanics who operated the machinery during the run. Sandage writes that “astronomers feared this informal assessment” by the assistants who rated their skills first-hand.

“Midnight lunch” broke up long hours of duty in the dark. Adams allocated each person on duty two eggs, two pieces of bread, jam and butter and coffee or tea. The night assistant got half an hour for his “lunch” then climbed to keep the observation going, while the astronomer descended for his luxurious 30 minutes.

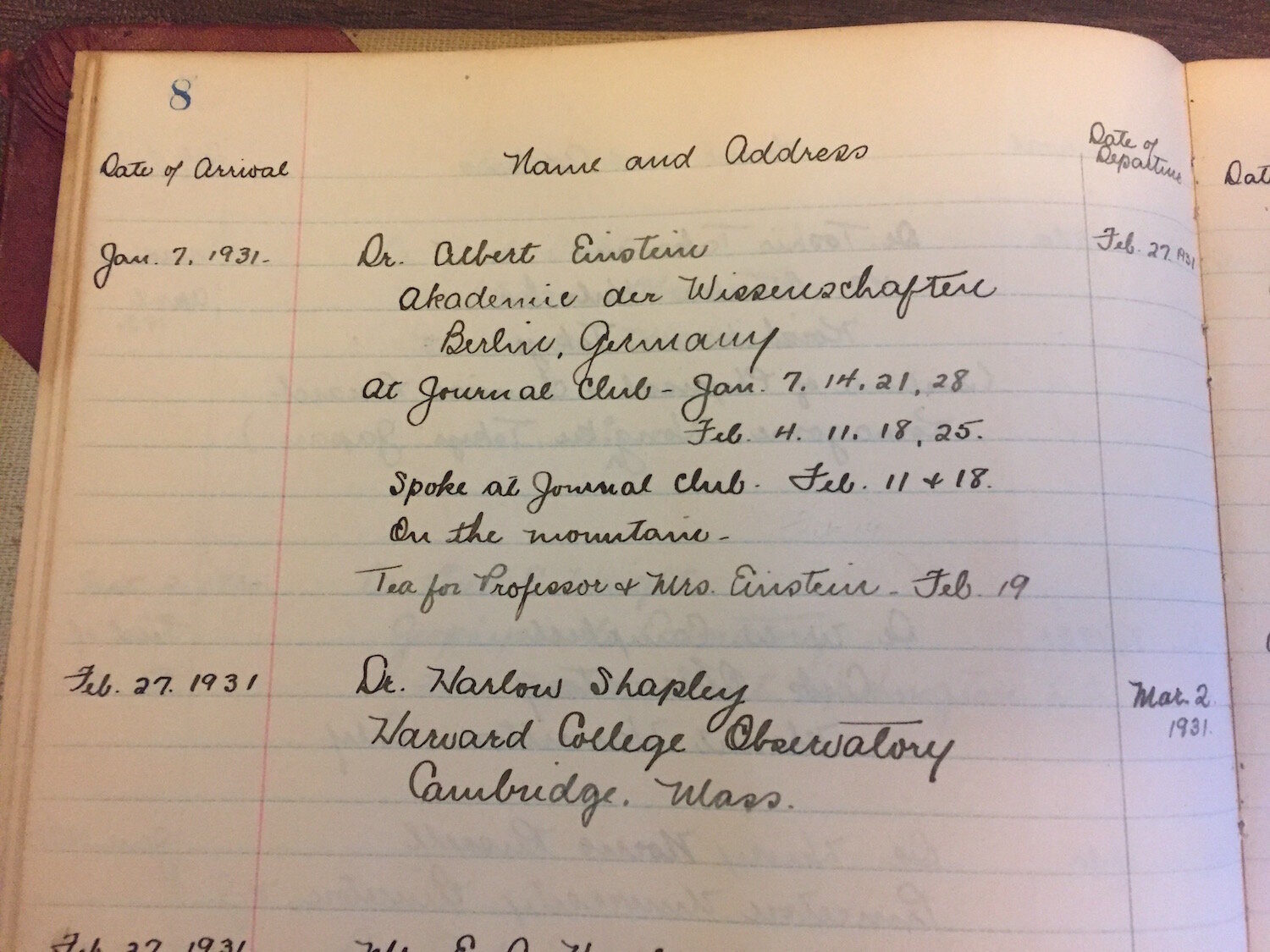

During their runs astronomers on the solar and optical telescopes lived at a small compound called the Monastery. MWI trustee Dan Kohne and Robert took me there in my second excursion up the mountain, by day. From 5,700 feet the views of Pasadena and the Pacific Ocean were spectacular. The dormitory spaces could be called - er - monastic. The men could gather in the little library and adjoining dining room. Sandage notes that at all meals required coat and tie; seating was in order of precedence.

Visiting the 60-inch telescope in daytime. Photo: Robert Anderson

Most of the work of astronomy was tabulation and mathematical analysis. Objects captured on photographic plates had to be labeled by brightness and size. The 60-inch telescope also captured the spectra of objects farther away than ever seen. Analysis of each tiny dot could reveal its chemistry and type. So recording what they found was a huge job. MWO had some “computers” for this but mainly the astronomers did it themselves.

Then they reduced data for each object of interest by entering it standard tables for comparison. Additional work was the mathematics of positions and orbits, etc. Shapley told Hale his twelve papers of 1917-1918 had 20 pages of tables and some 200 pages of text. He produced more in this series, and also important papers on very distant Cepheids and on eclipsing binaries. Those who worked with him then and later noted his “prodigious” output.

The papers had to be reviewed by colleagues, edited and published. By MWO no less! No mistakes or typos! The MWO publications editor was Frederick H. Seares.

Shapley’s wife Martha assisted him to some extent, though she had three small children on her hands. She later said she observed as well. But her obvious forte was mathematics. He credits her in several papers. Years afterwards, he would pull from his shelf with pride Mount Wilson Contributions No 160 and 161 of 1919 which they co-authored.7

The published findings from all this labor were and always will be the main legacy of MWO’s great instruments.

What of the data they produced? Cindy Hunt of Carnegie Science showed me around the offices, library and equipment at 813 Santa Barbara Street, the Carnegie -MWO office where everyone worked. She walked me downstairs to a black metal door “Moser Safe Co” that seals the trove.

She opened the door to show me the Carnegie Science collection of more than 250,000 glass plates from the solar and optical telescopes from the beginning. The larger plates imaged the sun - many with Hale’s drawings and hand-written notes - were fascinating. Worth another visit!

Hunt noted how many drawers had plates of the Andromeda Nebula, the nearest candidate as a neighbor galaxy in the northern hemisphere. What was it? A nebulous thing inside our Big Galaxy, as Shapley said? Or an “island universe” beyond, as some other astronomers contended though they had no detailed images.

Cindy pulled out the plate Hubble exposed on the 100-inch October 5-6, 1923. Comparing this plate to others taken on different dates, he saw that Andromeda contained a variable star, so it had to be far from even our big galaxy. There were other galaxies beyond ours! Hubble famously wrote on this plate “VAR!”8 Seeing it was the high point of my visit - and anyone’s, I expect.

Dan dove in the collection and found a sample plate taken by Shapley. Its envelope records the date taken, March 28, 1920, and coordinates, exposure time, viewing conditions, etc. The image is of M53, one of the most distant globular clusters that revealed to him the true shape of the Milky Way.

It is a wonder to us now how much information was gleaned from these crude images. Contrast it with the photograph of M53 taken with a good amateur camera by Russell Croman, on the ground in Texas in 2004.

***

I learned that astronomical observation in the early twentieth century was physically demanding. Success depended on endurance and precision in the cold dark dome, then desk work of tabulation, reduction and running the gantlet of observatory publication. The astronomer shared findings and drafts with peers, so a heavy correspondence was essential, too.

By the road to MWO

Author photo

While Shapley had friends at MWO, he was disliked by some others including Adams.

He was criticized for speculating too much, and “enormous vanity.” In his history Sandage calls the reasoning three of Shapley’s fourteen great papers “brilliant.” Then he takes apart other bits: “infamous,” “unwarranted speculation,” “wrong”. Shapley was accused of not crediting some others, though he was hardly alone in this. By all accounts, Hubble disliked him from the start.9

My hosts were not interested in old feuds. As to the merits, a non-astronomer cannot decode all the technical criticisms of Shapley’s prolific texts. In any event, he was willing to leave when the post of director of Harvard College Observatory became vacant in 1919. He was just 34 and perhaps too ambitious. But he sought the job and got it, with Hale’s blessing. As Director from December 1, 1921, Harlow Shapley had a broader chance to realize his gifts.10

Those who knew Shapley later –including me – found him a witty outgoing scholar with many interests. He did not forget his Ozark accent nor his Missouri farm roots. His deep interestin botany and geology informed his writing and public talks. (A 1922 paper is titled “The Origin of Life.” Headline for a 1928 lecture: “We are made of star stuff.”)In Missouri he had worked as a daily news reporter to pay for college. At Harvard he used his pulpit as Director to launch a radio series on science. He forwarded news of astronomy and other sciences to Science Service, which distributed its stories nationally He popularized the dramatic changes in cosmology by talks on … Hubble’s results! His liberalism may not have won friends in Monastery library discussions, but it propelled him to defy the House Unamerican Activities Committee in the 1940s. As a politically connected institution-builder, he helped to shape the National Science Foundation. The astronomers on the peak had trekked to the summit of knowledge. Only five percent of American college age men attended college. Fewer than 600 Americans were awarded PhDs each year. And Shapley’s doctorate was not plain vanilla. He earned it at Princeton under the great astronomer Henry Norris Russell, who admired him. At the Santa Barbara street office I gazed at the formal portraits of somber-looking men. I try to envision my grandfather among them as a Missouri farmer new to the game, albeit refined by four years at Princeton. I can visualize him not fitting in and I’m fine with the contradiction.

After he left MWO in 1921, two of Shapley’s key results were shown wrong. Data and theory were moving fast, especially once the 100-inch began yielding published results. Also scientists elsewhere jumped into the debate.

Don Nicholson, Mildred Shapley Matthews, & Dave Jurasevich at MWO in 2013.

Photo: Tom Meneghini

First, Shapley had computed that the Milky Way galaxy was 300,000 light years across - bigger than anyone thought. The story of his errors and upending by new data from 1930 is well-documented. Second, he contended this Big Galaxy contained the spiral nebulae - which were not certain to even have stars. But Lick Observatory astronomers (including Hubble, who trained there) said the spirals were “island universes” beyond. Between 1923 and 1929 as Hubble showed this, Shapley’s “evidence” collapsed. He “cried uncle” in the words of Marcia Bartusiak. Thereafter in his writing and speaking he promoted this new vision. He is credited with helping to win public acceptance of it, while building support for astronomy.11

Yet his being wrong contributed a lot to science. Hale arranged for Shapley to debate Lick astronomer Heber D. Curtis on “the scale of the universe” before the National Academy of Sciences in Washington DC. Their “Great Debate” of April 26, 1920 was inconclusive; Hubble’s definitive results were years in the future. Both men were partly wrong and both were partly right. The Shapley-Curtis dialogue has been used to teach the scientific method ever since.12

Possibly the most time I spent with my grandfather was in the woods of their property in Sharon, New Hampshire. He had studied plants all his life; hiking was a family activity. So none of us were surprised that his 1969 memoir was called “Through Rugged Ways to the Stars.” No surprise that this professor who dedicated himself to desk work, tabulating star tables, issuing scholarly papers and books, and committee work for dozens of organizations, would don his old hat, grab his little scythe for brush clearing and head down the trails.

On Mount Wilson I saw exactly where Shapley discovered his second scientific passion - ants. From the Shapleys’ home, hiking was better than a roundabout drive. In Rugged he writes:

“We had to be rugged in those days. We would go up the mountain, a nine-mile hike, sometimes pushing a burro, sometimes not.” Living on at the Monastery for the allotted “run,” he dove into the woods to collect shrubs.13

One day he noticed lines of ants running along a wall by the shop building. (p 65) He returned and found they ran slower in the shade or the cool of night and faster in hot sun. “I got a thermometer and a barometer and a hydrometer and all those “ometers,” and a stop watch.”

Shapley figured out how to determine the air temperature from the ants’ speed.

He consulted authorities in the field. Then he published papers on the thermokinetics of ants. These publications from 1915 to 1919 became classics in the field.

But he dared not show the papers to higher-ups at the observatory lest they think his effort was a “stunt.”

Shapley pursued his “harmless hobby” all his life.

In 2020, in Emily Simpson wrote in the Royal Society Notes and Reports Emily Simpson wrote <Shapley’s understanding of ant physiology and behavior had [an impact] on his own views relating to evolution on the cosmic scale.”14

The author searches for ants where Harlow Shapley found them 100 years earlier. Robert Anderson

Robert and Dan took me to the wall below the machine shop, where those trailrunners sparked Shapley’s life-long fascination.

In the hot sun, I searched along the wall.

No ants.

On the other hand, they could not have known we were coming. We hadn’t known either until ten minutes before.

Seems I’ll need to follow this trail of Harlow Shapley’s life some more, too.

I am grateful to many people who have helped me with sources and perspectives. Special thanks are due to Timothy J.J. Thompson, MWO Trustee and Docent, for reading the draft. Responsibility for the text is mine alone.

Sunset on the mountaintop. Author photo

Notes:

1 The HPWren TowerCam enabled the public and local authorities to track the Bobcat Fire that burned 115,800 acres of the Angeles National Forest, which includes Mount Wilson, from September to December 2020. The fire approached the MWO facilities but did not harm or disable them.

2 Kohne, Dan and Polyzoides, Stefanos, Eds. A Temple of Science: The 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, Mount Wilson Observatory, 2018. Pp. vii-5 and 60-61.

3 A precise account by its builder George Ritchey is G. W. The 60-inch Reflector of the Mount Wilson Observatory, Astrophys. Journ. 29 April, 1909 (198). Ritchey_1090ApJ__29_198R.pdf

4 Anderson, Robert, “Our Place in the Galaxy,” Reflections, Fall Quarter/November 2018, pp. 1,4,5,6, Smith, Horace, “Bailey, Shapley, and Variable Stars in Globular Clusters,” Journal History of Astronomy, Vol 31. 2000: pp 185-201.

5 Shapley, Harlow, The View from a Distant Star: Man’s Future in the Universe, Dell Publishing, 1963. Delta Book paperback, 1964. p. 2.

6 Sandage, Allan Centennial History of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Volume I The Mount Wilson Observatory, Cambridge University Press, 2004. 162-169. p. 187-193.

7 Shapley, Harlow, and Shapley Martha B., “Studies based on the colors and magnitudes in Stellar Clusters, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Papers,” Contributions from the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory Nos 160 and 161. Preprinted from the Astrophysical Journal, Vol. L., 1919.

8 Of many accounts, a brief complete reference is Kohne, D. and Polyzoides, S., op. cit., pp. 38-43.

9 Sandage, op. cit., pp. 303-311. An alternate view of the papers is offered by Horace A. Smith. “Shapley’s willingness to sweepingly interpret data led him to conclusions unreached by his older contemporary,” Solon I. Bailey, who had pioneered the study of globular clusters. Thus Shapley not Bailey brought about what Peter van der Kamp termed the “galactocentric revolution”, analogous to Copernicus’ heliocentric revolution.” P.185 of Smith, Horace A._JHA_xxxi_2000_pp._185-201.pdf.

10 Gingerich, Owen, “Harlow Shapley” in Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 12 pp. 345-352, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1975, pp. 345-352. Gingerich, Owen J., “Harlow Shapley and Mount Wilson,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Vol. 26. No 7 (Apr. 1973), pp 10-24.

11 Hubble reported his unfolding discoveries in correspondence with Shapley. He replied with questions and then conceded to the new evidence. “He cried uncle, acquiescing speedily and graciously,” per Bartusiak, Marcia, The Day We Found the Universe, p. 209.

Shapley went on to promote and win public acceptance the new model of the universe.

Dick, Steven J. The Biological Universe p. 57 “[T]he Einstein-Shapley-Hubble image of an enormous universe with the Earth stuck in a corner of one galaxy among billions formed an important background to all arguments on the plurality of worlds after the 1930s.”

12 Hoskin, Michael “Shapley’s Debate,” in Jonathan E. Grindlay and A. G. Davis Philip, The Harlow Shapley Symposium on Globular Cluster Systems in Galaxies, Proceedings of International Astronomical Union Symposium No. 126, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Holland, 1988. P.8.

13 Shapley, Harlow, Through Rugged Ways to the Stars , Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1969, pp. 51, 65-67. Re ants and evolution see View from a Distant Star, pp. 9-14.

14 Simpson, Emily, “Ant Mazes and Astronomy: Harlow Shapley’s Entomological Experiments at Mount Wilson Observatory and Pasadena, California.” Royal Society Notes and Records, doi:10.1098.rsnr.2020.0024.