By Deborah Shapley

Shapley’s Round Table:

A Memoir by the Astronomer’s Daughter

Mildred Shapley Matthews

June L. Matthews and Thomas J. Bogdan, Editors. 295 pages.

BookBaby, 2021 $20.00

Preface: Why this Book Matters

“I would often look out my window on the top floor and see two or four at play with the rubber ring on the deck tennis court next to the woods. Bart Bok, Fred Whipple, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, Martin Schwartzschild, to name only a few, tried their skill at this game.”

Mildred Shapley age 20. Betz Collection

This is one of many stories Mildred Shapley Matthews tells about life with father - her father Harlow Shapley. Shapley had won reknown for discovering the true shape of our galaxy at Mount Wilson Observatory in Pasadena, California. He moved east in April 1921 in line to be Director of Harvard College Observatory (HCO). He was 35 when he arrived at the formidable Director’s Residence built in the 1850s and expanded in 1892. His wife Martha and their three young children arrived soon after.

Mildred, born in 1915, was the Shapleys’ first child and only daughter. She was six when she arrived with her little brothers Willis and Alan and their mother. Harlow and Martha Shapley made a home there for their growing family, visitors, and HCO staff and students through his retirement as Director at the end of 1952. Afterward the Residence was torn down. The present Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory headquarters was built on the site afterwards.

I’ve been reading the literature about Shapley before, during and after his tenure as Director, through 1956 when he taught cosmic evolution as Paine Professor and as a famous public voice of science through the late 1960s I am another grandchild. My father was their eldest son Willis (1917-2005).

Shapley’s Round Table is a memoir Mildred compiled in the early 1960s. It has her interviews with her father, her own recollections, and narrative passages for a biography. The manuscript remained on the shelf so to speak, as she went on from 1970 to be editor of the University of Arizona Space Science Series of books, which extended to 30 volumes. She passed away in 2016 days before her 101st birthday. In 2012, she had happily accompanied her brother Lloyd to his Nobel award in Stockholm. (See Gallery below) Meanwhile her daughter June Matthews, after retiring as a Professor of Physics at MIT, and Thomas Bogdan prepared the manuscript for publication. (See About This Book below) They decided to leave Mildred’s text intact with light edits; Bogdan’s ample and amusing notes clarify and correct. The book has weaknesses - many of the science passages were left incomplete. But themes such as Shapley’s quickness, humor, idealism and his precious ants are true to life.

““Mildred’s book adds first-hand observations of a girl and young woman who knew the players in the Golden Era of HCO under Shapley.””

Mildred’s book adds first-hand observations of a girl and young woman who knew the players during the Golden Era of HCO under Shapley in the twenties and thirties. She married in 1937 and thereafter raised her family in California. In following summers the Matthews’ stayed at her parents’ 100-acre rural retreat in Sharon, New Hampshire. Her recollections of him and our family life in Sharon are another unique contribution of the book.

In this article I share what my aunt Mildred adds to the canon of literature about Harlow Shapley and others who worked at or visited this lively campus. She is a first-hand observer. She has a good ear - unsurprising given her violin and other musical skills. She’s witty and irreverent. She gets him to tell stories not told elsewhere.

I - CLOSE-UP RECOLLECTIONS

Harlow Shapley at lawn party with child nearby. At left is Henry Norris Russell. Shapley Matthews Collection

The literature reports the titles and research of those Mildred saw tossing the ring: Chandra had a three-month appointment in 1935; Schwartzschild was Littauer Fellow for three years. Bok arriving in 1929 and Whipple from 1932 left huge research legacies.

Such “stars” and all staff crossed paths among the offices, library, and on the sunny south lawn (now gone). The Shapleys welcomed them at the Residence for afternoon teas, evening events, Sunday chamber music. And sports.

“My father insisted on exercise.” He “brought deck tennis off the ocean liners to the lawn.”

“For many years my father was a champion player” at this game. He “used agility and he used psychology.” He’d look in one direction, other make a face so that we all fell down laughing and lost the game….”

“Outdoor tea parties usually ended in a quasi-baseball game on the south lawn.”. Later a “wealthy patron gave the observatory a genuine tennis court, and so the sporting life persisted.”

Telephone Bells, Winter Boardwalks

”We children were fascinated by the observatory telephone system, whose bells could be heard throughout the house, as well as in the observatory buildings.

Willis, Mildred and Alan Shapley on south lawn of the Residence, ca 1922. Shapley Matthews Collection

“My father’s call was one-three, his secretary Miss Walker’s was two-two; my mother’s was three. The observatory staff each had a number….”

The formal front entrance was a whole story below the main floor. A visitor pulled the knob which made a different sound. “We didn’t have a cook nor butler.” So one of us would come thumping down the stairs to see who it was.” Paul was the handyman Harvard sent once a year to update something in the house, such as changing more gas lights to electric.

A special friend was Michael “the old observatory gardener.” He eyed them playing under the huge rhododendron by Building C; they might break the branches. They fought grass battles with his lawn cuttings.

Best was “when winter was near and it was time for him to put out the boardwalks -150 yards of them - over the maze of dirt paths. They were all lettered and numbered and thus not hard to arrange in their proper places…. As soon as he had finished laying down the boards, the snow came and the season of shoveling and sanding began. At the end of the winter the reverse happened. We’d watch him re-label the sections, disassemble them and stack them away. When the job was completed, spring would promptly arrive. Michael never failed.”

[I note: Michael’s boardwalks enabled people to walk among the buildings in winter.]

Cannon’s Peal of Merry Laughter, Russell’s Cracking Voice

Annie Jump Cannon was right off the children’s favorite on the staff. Mildred recalls “an ageless woman of large and shapeless form.” Jump was “something she could not do.” She was “loved by old and young, No party was complete without her.” She was “an excellent conversationalist” mainly by lip-reading. Her ‘peal of merry laughter” rang through the house.

“We often ran to her when shyness overcame us at a tea party. She would hug and kiss us on the backs of our necks and always had something nice to say.”

Their frequent sleepover guest was Henry Norris Russell of Princeton. Widely regarded as the dean of American astronomers Russell had engaged Shapley for doctoral study and supervised his groundbreaking thesis. Once his former student became Director of the larger HCO, Russell became an influential advisor.

He was “a tall, erect man giving the appearance of being stiff and dignified.” She describes him as full of conversation and limericks and enthusiastic at charades. He amused the children by creating origami paper figures. When Russell was seated, by him was set a pitcher of water and a glass. As he “told stories and matched wits with my father” Russell drank glass after glass “as if he were trying, in vain, to wet down his dry cracking voice.”

STORY CONTINUES ⥥

Mildred Shapley, Helen Howarth, Annie Jump Cannon, Willis and Alan Shapley. Shapley-Matthews Collection

Merry-go-round Desk, the Revolving Life

“The residence and the main buildings of the observatory were all connected.” From the Residence main hall, “you could walk directly into Building A. “ It had offices, a library; the Great Refractor and the Coudé telescope. A “covered bridge” let you pass from Building A to Building C which housed the valuable plate collection and offices including the Director’s.

Shapley took over his predecessor William Pickering’s office and revolving desk Mildred recalls it was crowded with papers. On Sundays “we would go over to his office for a ride on his merry-go-round desk.”

Harlow Shapley’s rotating desk. Harvard College Observatory

The circular table had spaces for twelve different jobs.” Above, a bookshelf with compartments rotated. Mildred had lots of chances to study the shelves close up.

The multifaceted Director “collected objects without restraint….books, cigars, fossils, …bottles of ants preserved in alcohol. (Is this where he stashed the vial of ants he famously took at Stalin’s banquet? (See Stalin’s Ants) His chair swiveled to face a conventional table which was covered with even more work. Next to his chair stood his Dictaphone and the inside and outside telephones.”

Working On the Go

Arville D. Walker Shapley’s secretary. “In all situations she maintained a calm and solemn face.” Photo: Harvard Observatory Images Fine paper doll.

Upstairs in the Residence at night, Shapley could dictate correspondence on the Dictaphone there. At breakfast he brought papers to the long dining room table. Then he took the papers and Dictaphone wax cylinder “over to his office in Building C” chatting with staff as he went and “giving Miss Walker and her assistant a full morning’s work.”

Shapley had appointed Arville D. Walker of the computing staff as his secretary. She and various assistants typed everything that “HS” did not type himself. Shapley mainly speed-wrote by hand in Gregg’s shorthand, which Miss Walker typed unerringly. She was a Christian Scientist who never missed work because she was never sick, Mildred writes. She stayed in this role for three decades.

Family Helps Out

The literature records that Shapley started Open Nights when anyone with a ticket could enter the dome of the Great Refractor. They could look through the famous telescope and hear more. From Mildred we now learn it was a family operation.

“I can see [Willis and Alan] in their dark serge suits, guiding the visitors up the creaky circular stairs that led to the green dome, or standing before the illuminated transparencies in the meeting room after the lecture….

“My brothers would be ready with answers to: Why do the stars twinkle? Do the canals on Mars contain water…These were questions not too difficult for the sons of the director, especially as it was allowable to say, “Astronomers don’t know the answer to that question yet.”

“My father liked to seek out his colleagues in their offices. There he could sit and discuss a work [matter] with less interruption and with less tension, perhaps, than in his director’s office.

When the telephone system was out once, Mildred was sent over to bring him to dinner. But “Dr. Shapley has misplaced himself somewhere,” Miss Walker says. Mildred finds him in Miss Cannon’s office and is roped into a story Cannon tells them. “Then we noticed Willis had joined us to give a second call to dinner.”

Music

My father, who couldn’t carry a tune, or maybe he could but wouldn’t, was continually encouraging music.” They held Sunday chamber concerts to which everyone was invited.

Martha Betz Shapley had played piano all her life. The book describes her family of German heritage through which she learned music (piano), science (math), and sports (basketball). At the 60 Garden Street Residence she started Mildred on piano (later violin), Willis on flute, Alan on cello. Lloyd, born in 1923, started piano. Carl, born in 1927, acted as conductor.

The formal record shows Shapley encouraged amateur observers - brought them into the Observatory offices. The Amateur Telescope Makers of Boston held meetings there. It was discovered that one of the men was a professional pianist, whose ‘interpretation of Chopin was superb,” Martha Shapley hired him to teach piano to Mildred and then Lloyd.

Shapley Family Orchestra at 60 Garden Street Residence, December 1951. Martha and Lloyd Shapley are at the piano. From left: Alan Shapley and June Matthews on cello, Ralph Matthews on bass, Mildred Shapley Matthews on viola, Sarah Shapley on flute, Bruce Matthews on violin. At rear is Willis Shapley on flute. The two children are Melvin Matthews (right) and Deborah Shapley (left). Shapley Family Collection

Mildred has an ear for the music, the players, and how they did. “Since Hayden was dead, why not try his Toy Symphony?” The musical talents of the women astronomers are profiled. Frances W. Wright “played the piano like a house on fire.” Jenka Mohr, “one of his able assistants in galaxy” work was a fine enough violinist to pair with Einstein (See below). Cecilia Payne displayed a “beautiful soprano voice.” We learn that Bart Bok once took up the mandolin. They needed a bass, so a student William Liller built one they called “George.”

“We’ll invite everyone.”

Mildred portrays her mother Martha Betz Shapley as a devoted and excellent manager of a short-staffed household, with the doors opened often for teas, dinners, parties.

Her father suggests they have a party on Friday. She asks: How many? 25? 75? “We’ll invite everyone,” he says.

A poster would go up such as COME IN RAGS OR OLD_FASHIONED to celebrate raising the funds that became Building D. Miss Walker would hand out notices in case the poster was missed.

Martha Shapley calls extra maids to come over. She and the family pitch in. The sandwiches and cakes are set out on time.

Music made for dancing. Shapley’s favorite was the Virginia Reel, “a sober kind of square dance in which anyone could participate.” Couples start off in lines facing one other. Shapley had the guest of honor lead off taking the hand of Annie Jump Cannon as his partner.

At the time, Cannon had classified spectra of perhaps 200,000 stars. Her system OBAFGKM (based on earlier Harvard work) was adopted internationally in 1922 and is still basic to astronomy. The young Mildred watches in admiration.

“She did it with the grace and dignity of a queen…Miss Cannon didn’t jump or dance but when she led the Virginia Reel she was in her element.”

In the formal literature parties sound only frivolous. Women and men dancing? Costumes? The Director choosing teams for charades? Mildred shows they were inclusive: women, youngsters, students, staff, notables. “The famous and the humble came, sometimes in the same person.“

“Never expect a decent salaree”

Mildred was 14 when Ms. Walker brought the libretto of “Harvard Observatory Pinafore” from the Library to Shapley. He was looking for something special for the American Astronomical Society meeting at HCO over New Years’. The libretto had been created in 1879 by a junior staffer Winslow Upton spoofing Gilbert & Sullivan’s wildly popular Pinafore which had opened in Boston the year before.

The original Pinafore is a British takedown of “the Ruler of the Queen’s Navee.” Upton’s rewrite spoofs Observatory Director Pickering by name. Mildred speculates it was not performed because Pickering had become Director just two years earlier and was Upton’s boss.

Fifty years later Shapley, with his family retinue of Gilbert & Sullivan fans and delight in wordplay and satire, had no inhibitions. Frances Wright and others were consulted if it could be done. A cast was agreed. All but one were from the observatory staff. Plus Mildred.

[Shapley may have chosen the Pinafore project for morale. In the final weeks of 1929 everyone got terrifying news by radio and letters. The Great Crash in London was spreading; Black Tuesday on October 29 kicked off massive shrinkage of the US economy. At HCO, no matter how the show went on Dec 31 people would feel brightened by humming and singing the harmonies and clever lyrics around the campus.] Mildred writes:

“Wright was our tireless accompanist keeping us in good rhythm while Jenka Mohr kept us on pitch with her violin.” They rehearsed “as though the observatory’s fame was in our hands,” Mildred writes.

On Dec 31 “about a hundred” American Astronomical Society guests came for a New Year's Eve party, The “Harvard Observatory Pinafore” made its debut at last. Thunderous applause. But midnight was near.

“As the ticking of the Observatory clock, connected with a sounder in the room, warned…of the approaching end of the Old Year, all stood at attention, my brother Willis played taps on his flute at the exact moment Professor King sounded the midnight bell, and everyone wished everyone a Happy New Year.”

“Observatory Pinafore” cast with the Director. Boy lower left is Willis Shapley. Girl next to him is Mildred Shapley. Boy at right is Alan Shapley. In back row woman to left of Harlow Shapley is Arville D Walker. Harvard College Observatory

After this and a second performance on Jan 13 they went back to normal work, Mildred writes. “But the lines that describe so deftly their customary attitude kept the astronomers laughing at themselves long after the show was over. “

“’ He must open the dome and turn the wheel,

And watch the stars with untiring zeal.

He must toil at night though cold it be,

And he never should expect a decent salaree.’”

She quotes Yale astronomer Frank Schlesinger: only Harvard could have put on such a show.

The Lowells’ Secret Discovery of Pluto

One joy or burden of being Director was to figure when sightings were “ghosts” or correct. Shapley’s account of one particular discovery may be unique to this book. Shapley tells his daughter. Story Continues ⥥

Are We Quite Alone?

“One day, Roger Lowell Putnam [the boss and trustee of the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff Arizona, which was founded by his uncle Percival Lowell] came into my Cambridge office in an excited state. He looked around carefully to see that we were safely alone. Then in a horse whisper said: “I think we’ve got it!” Influenza? Religion? Or just what?

“This was about February 10, 1930. No he said I think we’ve got planet X!” For some years at Percival Lowell’s Flagstaff observatory they had been looking for the hypothetical planet X. A special telescope had been made and mounted and manned by the farm boy amateur astronomer Clyde Tombaugh. He had made and examined hundreds of plates searching for the photographic trail of … the ninth of the solar family. Now they had something, and in order not to lose credit for the discovery, Roger Putnam had me record the day, the hour, and the minute of his announcement to me.

“Don’t tell anybody - not even the family.’ But suppose I talk in my sleep? Why the delay in making this exciting announcement? They wanted confirmation with more plates it was stated and wanted to get an orbit computed -- and some other excuses were made for a delay that I could not quite understand.

“Finally, the announcing telegram came, and then I knew what these sentimental astronomers were waiting for; it was the March 13 birthday of Percival Lowell. Although he had died some 15 years earlier, Percival Lowell was on the job – his inspiration had put it across.”

When the discovery of Planet X was revealed “[w]e had a Trans-Neptunian party - strange clothes, strange language. Dr. Payne and my father talked in a Trans-Neputunian dialect. Somebody composed a song and music “in an appropriate style. Everyone was there. Even the staid and proper Agassizs…came with pleasure and George Agassiz sang nobly in his whisky tenor.”

Images from Lowell Library Archives. Montage and caption by the author.

Blind Ants in Caps and Gowns

Shapley’s performance in the 1920 “Great Debate” on the scale of the universe with Heber Curtis (which Mildred recounts) was less than stellar. His speaking style took off as he took the helm of the observatory. He spoke to the 1924 banquet of the American Association of Variable Star Observers “in words that flashed and glittered” the recorder wrote. He was invited to the AASVO banquet thereafter, Mildred writes.

Benjamin N. Cardozo, Associate Justice, US Supreme Court JRank Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

He asked Mildred, then 17, to accompany him to two commencement addresses he was to give at Brown University in Providence and in Philadelphia on the same day. Also on the dais at Brown hearing Shapley’s address was Benjamin N. Cardozo, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. The justice was on the train the Shapleys took to Philadelphia; he asked to borrow Shapley’s text so he could himself deliver it to Penn law school graduates that day. It was “much needed by beginning lawyers,” Cardozo said.

Mildred likes the xx word speech too and reprints it. On Running in Trails reflects Shapley’s fascination with ants and the lessons of insect societies. The Dolichoderinae run in the same trails for generations. They are “static and blind” whereas “the world of the primate…is cosmic.” His is “an expanding environment, made so by himself.”

Universities are not for conformity. He defends the “abnormal” student who may not fit academic norms whom a university should encourage. “When a subject is properly approached, study and research will be the same word.”

Nine decades on, his talk is a tour de force even on the dry page.

The Universe at Breakfast

The Residence dining room had a long table with ten high-backed chairs; they toppled backward if you weren’t careful. Mrs. Shapley ran a tight ship with everyone seated for meals.

“One morning in 1932, the Universe came to our breakfast table. I remember my father un scrolling a scroll one yard long and 2 feet wide as we moved aside the food and dishes and wanted to know, “What is it?” The four corners were held down with water glasses.

One of the pair of definitive maps of the brightest galaxies published in the Shapley-Ames Catalog. Shapley, H. Annals of Harvard College Observatory. Vol_88 (2)_1932, p. 64.

Spotty Maps

“There’s your Universe as of right now,” he said. “We put the finishing touches on it last night.” Here was a diagram of the Shapley – Ames Catalogue of 1249 external galaxies. “Each symbol represents a galaxy like our own Milky Way system.”

We began asking questions. “What are the circles?”

“The open circles are the bright galaxies brighter than magnitude 12 – the dots represent the galaxies between 12th and 13th magnitude. The bigger the magnitude number, the fainter they are.

“And this curvy line?”

“It indicates the central line of the Milky Way. You can’t discover many external galaxies there because we are inside our watch shaped galaxy looking towards the edges and our view is pretty well obscured by Milky Way dust. If we look up or down from our inside position, we have a better chance of seeing through and beyond. Notice these groupings?”

“Clusters of galaxies?’

“Yes, this spottiness is interesting, isn’t it?” My father began rolling up the universe again so that the maid could serve the coffee.

“And now what do you do?” I wanted to know.

“Breakfast,” he replied.

“No, I mean about the Universe.”

“Go deeper - begin looking for and cataloging the fainter than 13th magnitude galaxies…And we must study these groupings. It appears that galaxies gravitate and move in groups.”

The pair of maps illustrated the Shapley-Ames Catalog of Bright Galaxies - the first compilation of galaxies in the northern and southern sky. The catalog contains position, brightness, size, and Hubble classification of 1249 galaxies brighter than 13th magnitude. For 60 years, it was the primary source for information about redshifts and galaxy types.

A key finding was their irregularity. The Virgo group they identified was so big to be a ‘supercluster.’ Local clusters and groups posed a cosmic question: How could matter be spread unevenly in the universe? Mildred notes her father’s continued push to record and publish data on dimmer galaxies with HCO’s northern and southern telescopes. Shapley’s Round Table includes an article by Owen Gingerich about this work. (See About This Book.)

Adelaide Ames Harwood Collection, US Naval Observatory

Death of Adelaide Ames

“’Pop, the phone is for you - long distance, I think.’ I had answered the telephone as we were about to go into dinner.

“He took up the receiver, said ‘yes,’ listened a moment and then - ‘Jesus Christ. No!’ He slammed the receiver down and just sat there by the phone.

“I had started to go but the conversation was so short that I was still beside him. Finally he got up. ‘Adelaide Ames drowned this afternoon.” He said no more - gave no more particulars - he hadn’t waited to learn them. An hour later he and Colonel Ames, the stricken father, were on the long ride to Squam Lake in New Hampshire.” - Mildred Shapley’s Round Table p. x.

Ames drowned while boating with a friend at Squam Lake, June 26, 1932. Shapley closed the observatory immediately. He and Col. Ames poled the lake to look for her body.

LeMaitre at Bridge

The International Astronomical Union’s 1932 meeting was held at Harvard. To host 350 international guests, “All the Shapleys were drafted for work.” Royal Sir Frank Dyson laid the cornerstone of Oak Ridge, Sir Arthur Eddington lectured, and everyone went out for the solar eclipse on August 31. Mildred (who was 13) recalls “three big luncheons in the residence” and “a big party” at the end.

Story Continues ⥥

Reversed-Collar Kibitzer

“LeMaître offered to take my bridge hand, pairing up with Father O’Connell when I was called out of the game by a late guest or something. Oh no,

no, I said to LeMaître, don’t bother, for while watching our game, he had pointed to the five of diamonds and asked, what do you call him. I told him, and later he pointed in the same inquiring manner to another card and asked, what do you call him.

“Why father, we call a spade a spade – it is the seven of spades. ‘Ah so,’ he said.

“Therefore, I was reluctant to impose on the other three by giving LeMaître my hand. I should not have worried for I soon noticed from a distance that the opponents, Mrs. Carol Reiki and Arthur share, Harvard graduate students, seemed to be having a hard time of it playing against the two reversed-collar men.

“Later looked more closely and saw a sweet look of triumph on LeMaître’s face. He had just bid and made a small slam, with queen high! It takes an expert to bid such a hand and successfully play it. He dropped ace and king on the first and only trump lead. Naturally I was amazed at this performance – this skill by the What you call him? kibitzer.

“Father O’Connell saw my dismay and puzzlement. He came up to me and said, ‘Perhaps I should explain that LeMaître is a much-experienced bridge player, and his inquiry about those cards was simply his seeking names in English which he knew only in French.’”

Georges LeMaitre in 1934. Technology Review.

LeMaitre at HCO

The Belgian priest Georges LeMaitre is the inventor of the theory of the expanding universe. A gifted mathematician, he was fascinated by Einstein’s work on relativity and observational work in the US. In 1927 he published his theory of why matter would be flying apart and, going back in time, start from a single [atom]. His paper was discovered in 1930 on the heels of Edwin Hubble’s breakthrough publication showing that galaxies were flying apart faster with distance. LeMaitre’s next big paper in 1931 proposed the universe had sprung from a ‘primeval atom’ - an idea later known as the Big Bang.

In 1930-31 LeMaitre was in the press for having corrected Einstein though the priest’s work was not widely accepted.

Astronomers now refer to this revolutionary model of the universe as the LeMaitre-Hubble expansion. LeMaitre had set out the mathematical-physical reasons and Hubble provided proof that it occurs.

Less known is that in the 1920s LeMaitre often visited Harvard College Observatory “to work with Harlow Shapley on nebulae” while getting his PhD at MIT. He also traveled to Vesto Slipher’s and Hubble’s observatories. At HCO he likely looked at galaxy distributions being mapped by Ames and Shapley. LeMaitre’s 1931 paper posits how the irregular distribution of matter came about. - DS

“Enthusiasm for life and for people” - Einstein

In 1935 Albert Einstein famously accepted the Shapleys’ invitation to stay at the Residence should he accept Harvard’s offer of an honorary degree at commencement. Shapley’s letter promised privacy. They would have an evening of chamber music if he brought his violin. Shapley greeted Einstein (with violin) at the train station where they tried to avoid the mob of photographers and took a cab to the Residence.

The children were told to act natural and keep quiet. But little Carl was too young to know better and asked Einstein why he did not cut his hair.

Privacy had been promised, Mildred writes, so only a few guests were invited including musicians from the Observatory family and friends.” The staff had the makings of several string quartets but lacked a suitable cellist. Jenks Mohr recruited a bassoon player from the Boston Symphony Orchestra who was a fine cellist (and demonstrated his bassoon).

Einstein “played an excellent first violin especially in the quartets of Brahms and Hayden. He and Miss Mohr did a Bach partita for two violins.”

Albert Einstein with violin and Harlow Shapley, 1935. ESVA Einstein, Albert C6. OBJ Datastream.jpg

He “happily listened to other players.” A Harvard professor and Boston banker at the piano did some high-speed sight reading of four-handed Bach “each smoking his pipe furiously as they went along.”

“At one point Dr., Einstein turned to me, observing, ‘I notice in your father such an enthusiasm for life and for people.

“’But you on the other hand have a quiet nature. But you are young.’

“I was full of emotion and joy for this evening…but…I could give Einstein only a smile and a nod.”

II - WAR and POSTWAR

Shapley’s Round Table includes many of Shapley’s wartime and post-war achievements. Here I share pieces of the story that seem unique; he spoke freely as they sat in their house at Sharon or tramped the trails. Because her manuscript was incomplete, I fill in some background so today’s readers “get” the twists in the story and his personality.

Shapley’s work in the 1930s and 1940s to organize US academic posts for scientists fleeing the Nazis is mentioned. [The intensity and scope of this work was signaled much later when files were available. At the time, those like Shapley who aided the “rescues” helped their cause by being discreet.] In any event, the photo shows three well-known “rescues:” Richard Prager, Sergei I. Gaposchkin and Luigi Jacchia.

The "foreign" group at HCO, 1939-astronomers, research assistants, and graduate students; left to right: top row---George Z. Dimitroff, Bulgarian; Cecilia H. Payne-Gaposchkin, English; Luigi Jacchia, Italian; second row---Donald MacRae, Canadian; Zdenek Kopal, Czech; Richard Prager, German; S. I. Gaposchkin, Russian; third row---Shirley Patterson, Canadian; Marie Paris Pishmish, Armenian-Turkish; Odon Godard, Belgian; front row, seated---Bart J. Bok, Dutch; Jaakko Tuominen, Finnish; Massaki Huruhata, Japanese; Luis Erro, Mexican. Photo and caption: Shapley’s Round Table from Shapley, Harlow Through Rugged Ways to the Stars. AIP/ESVA.

War. Building Peace through Astronomy

With the US in the war, travel and communication nearly stopped; HCO had no students and most staff enrolled in war work. Mildred notes that her mother took a job at MIT doing top-secret computing of “ballistics, shock waves” and other things. Martha Shapley continued in this job, doing other computational work such as meteor trajectories, for 13 years in all.

“The progress of science” required that observers all over, including behind enemy lines, send observation reports to the Harvard Observatory clearinghouse. Since the 1920’s the HCO telegraph service distributed reports to subscribing observatories all over the world. During the war, military censors blocked suspicious-sounding cables. So an instruction to all to watch for a nova flareup, sent to all southern observatories, could not be worded SHOOT NIGHTLY USING WHOLE BATTERY. Story Continues ⥥

South Africa Loss

The image series’ taken on HCO’s battery of telescopes at Bloemfontein, South Africa were uniquely able to record the southern sky. They were needed for research and HCO’s lodestone of continuous plate records dating to 1927 in South Africa and earlier from Peru.

Mildred quotes two Directors’ Reports [covering 1943 and 1944]. Most staff of the Bloemfontein station left for the war, though jobs were held for their return. But observing continued. Shapley wrote that fresh glass plates arrived on ships traveling “at unrevealed times by unrevealed routes to unspecified South African ports.”

The following report is titled “Disaster at sea.” The S.S. Robin Goodfellow had sunk in July 1944 en route from South Africa to North America. It carried important war material and a shipment of plates with images taken on the Bloemfontein station telescopes. “Apparently there had been engine trouble before the ship left port, and possibly a subsequent dropping out of convoy….”

“The loss was totally unexpected. The insurance rates for trans atlantic shipments had dropped to a very low figure and our shipping advisors had assured us of the relatively high safety of shipments by sea.” [i.e. relatively higher safety of shipping made lower insurance rates.]

The loss amounts to “something less than 20 % of a year’s of work.” [He added “we deliberately avoid shipping home plates made with the patrol cameras” whose “essence is continuous coverage of the sky throughout the year, and time cannot be replaced.”] Bracketed quotes included for clarity.

STORY CONTINUES ⥥

Mexico, InterAmerican Science

Credit: Wiki Mexican President Avila Comacho in 1940

Mexican Luis Enrique Ecco is in the 1939 foreign astronomers photo. Subsequently Mexican President Avila Comacho asked HCO “to help build a new observatory.” Shapley set in motion plans for loans of equipment. A new Schmidt reflector was built by Bulgarian George Dimitroff, also in the photo.

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 appeared to quash the project. Then, Shapley tells Mildred, by special night train arrived Ecco - now a diplomat - to convey President Comacho’s instruction that the observatory project should proceed.

In March 1942 instruments and books arrived with Dr. and Mrs. Shapley and some 30 astronomers for dedication at Tonanzintla, in Puebla. Return visits by Shapley and others strengthened astronomy in Mexico and diplomatic ties.

[Today the Tonanzintla Observatory or OANTON is still going. The website says its 28-in Schmidt camera was built at Harvard College Observatory. It enabled important work by Guillermo Haro the leading postwar Mexican astronomer.]

Shapley helped found the Committee on Inter-American Scientific Publication as part of his extensive work with Science Service. This enabled Latin American scientific papers to be read in the US and provided surveys of important developments to more than 1,000 Latin scientific publications.

Another Shapley-Science Service project was Science from Shipboard, a readable little paperback of celestial sights and navigation, carried by thousands of servicemen.

Celebrating Copernicus’ Revolution and Freedom

Poland had been invaded by German forces and partitioned with the Soviet Union. Hundreds of thousands of Poles were fleeing, starving, dying. Poland’s autonomy and freedom was a rallying point. Harlow Shapley was the scientific heir of Nicolaus Copernicus, the Polish monk whose book de Revolutionibus showed the earth and planets revolved around the sun. The revolutionary text had been printed in 1543, the year Copernicus died.

Shapley arranged a huge 400th event in Carnegie Hall in 1943. He tells Mildred of the “contemporary revolutionaries” who came including Henry Ford and Igor Stravinsky. Albert Einstein’s speech was “incomprehensible - so everybody loved it and him.” Shapley read a statement of support from President Franklin Roosevelt.

Copernicus quadricentennial Credit to come

He did more than rally US support for a crushed people and culture [I add: It was like rallies for Ukraine today]. In the 1920s the HCO had “loaned” a no-longer-needed telescope to Poland. Shapley arranged for another telescope — the famous 8” Draper on which Cannon worked out stellar spectra — to be sent to Copernicus’ town of Torun after the war.

Irish Telescope a Blueprint for Peace

The ADH Telescope Baker-Schmidt camera began operating in 1950. http://dasch.rc.fas.harvard.edu/telescopes.php

Shapley often spoke proudly of his initiative that resulted in the Armagh-Dunsink-Harvard (ADH) telescope addition to HCO’s Bloemfontein station.

During a flight stopover at the Shannon Airport in 1946, Shapley got himself introduced to the glamorous First Tarasoveich of Eire, Eamon de Valera. He proposed on the spot (astronomer Otto Struve is a witness) that a new telescope be built and jointly operated by the (warring) Protestant Northern Ireland and Catholic Eire.

Shapley says - as he often did - that the agreement that resulted was a testimony to civilization. Mildred says he believes it is “symbolic of the willingness and desire to cooperate across religious and political boundaries when something as remote and pure as the stars is concerned.”

Shapley tells Mildred of his later visits with Irish leaders helped by the Irish astronomer Eric Lindsay, an HCO alum who had married Sylvia Mussels, an HCO computer. De Valera was mathematically inclined, and in 1960 wrote Shapley asking which were the best textbooks in “algebra, calculus and geometry” and “mechanics and theoretical physics,” for example.

Stalin’s Banquet. Poulkova Ruin

Shapley through Mildred Shapley recounts “the Russia story” - his famous trip to the Soviet Union in June 1945 as head of a delegation of 16 scientists to celebrate the 220nd anniversary of the Russian Academy of Sciences. [Germany was collapsing; the Soviets had taken Berlin.] When Shapley was later accused of being pro-Russian, he retorted “the Russians did not invite me. They had liquidated some of their best astronomers, friends of mine.” President Conant asked him to represent Harvard and the State Department arranged his travel. Story Continues ⥥

Infamous Banquet

Mildred lets Shapley tell his story about the delegation’s so-called banquet with Stalin. During the four-hour feast, Lasius niger “dropped off the flowers or bananas or whatever decorated our table” and started crawling directly toward Stalin.” Shapley reached for the corked vial he kept in his pocket. “With a wet finger [I] gathered up the ant and put it to sleep” in the vial’s alcohol. Then - suspense - “another ant dropped off and went for Stalin.” Shapley put it in the vial also.

In this version of the tale he reveals that Stalin was nowhere near Shapley and the ant-laden table décor. The four-hour feast was for 1,100. The Americans “were seated about twenty yards from the government.” [Stalin was in no danger from the ants and Shapley did not rescue him.]

At home he kept the vial handy in an upper compartment of his desk. Showing it off later, he saw the vial had only one ant! Not two! What happened? [I can vouch that, at this point of his telling, everyone would be laughing.] He drew out the suspense for his wife’s answer: People who go to vodka parties can’t count.

There’s new news! Thanks to this book project E.O. Wilson revealed the answer. (See About This Book)

STORY CONTINUES ⥥

Shapley tells of a solemn moment of the 1945 Russia trip. The visiting astronomers traveled to the revered Poulkova Observatory near Leningrad. “Sir Harold (Spencer-Jones, Britain’s Astronomer Royal) and I stood on the rims of the great shell craters that marred the beauty of Poulkova Hill. The German armies in their fierce and bloody drive towards Leningrad had been stopped short…by the Russian resistance….The observatory was a ruin….There was no question Poulkova should be rebuilt.”

“With the leading Soviet astronomers present, we planned for the future - planned as we walked among the huge dandelions, which may have owed their size to soil enriched by human blood.” Story Continues ⥥

Penicillin Project

A plan for a pilot plant in Moscow to make penicillin as a friendship gesture collapsed. Shapley was approached by some Boston philanthropists to head a campaign to ‘give” such plant. It would help the recovery of “five million wounded servicemen” in a country which sacrificed more millions of lives to “save the Western World.” [The US created and distributed this wonder drug in the war years.]

Why me, Shapley asked? You are a natural organizer, they said. He said: You need national leadership - ask Eleanor Roosevelt. They replied: We did and she declined!

So I took over and set out a beautiful plan.” Then the Cold War closed in, donors withdrew and “we… folded up.”

Rankin: “Held HUAC in higher contempt than anyone”

Mildred moves quickly over Shapley’s efforts from 1944 on to form what became the National Science Foundation in 1950. She mentions his push for civilian control of atomic energy, allied with many who had built the Bomb, that became the Atomic Energy Commission.

In 1945, in San Francisco, delegates gathered to craft the United Nations to carry out the new global order. She writes that Shapley wrangled delegate Archibald McLeish by phone to include science in the mission of “UNESCO.” So the agency was born as UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Mildred traces this train of activity to his belief that wider education could forestall problems. She quotes one Shapley pitch, “Education toward International Tolerance” in the June 1944 issue of Tomorrow magazine. An excerpt:

“In an integrated world, education on an international level [must be encouraged and sustained]. Knowledge begets social understanding, which in turn, generates the generosity of spirit that restrains blind primitivism.”

““Knowledge begets social understanding, which in turn, generates the generosity of spirit that restrains blind primitivism.””

Shapley’s post-war political activities are told quickly. He was often in the headlines and wrote in the popular press. He became hero for liberals and defiant bait for right wing.

In 1946 Shapley’s correspondence with a peace group ICSAAP got him subpoenaed to appear before the Investigations Subcommittee of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Harvard sent a lawyer, Thomas Eliot; they brought a stenographer, not trusting the committee’s recordkeeping. In the chamber, Rankin presided alone. He kicked out the lawyer and stenographer. Shapley began taking notes while being interrogated. He explained that the charges were outside the committee’s jurisdiction and baseless. anyway Rankin ripped his notes away.

They emerged to a gaggle of reporters. Shapley repeated that the charges were baseless. The committee is a “Star Chamber” using “Gestapo tactics.” Mildred notes the press coverage favored Shapley. Immediately afterward 1,200 Harvard students signed a statement of support.

St. Louis Post Dispatch November 14, 1946 reports Shapley’s and Rankin’s angry remarks after closed hearing of HUAC investigations committee. Graphic: SophiaOjha.com

Rankin told the reporters “that man has held the House Un-American Activities Committee in higher contempt than anyone else has ever done.”

Shapley said to Mildred, “I considered this a very high compliment.” [But at the time the shadow of accusation fell on him, the family and some associates, even as Shapley, starting the next day, called for the abolition of HUAC. The HUAC continued to target other scientists and scholars, Hollywood stars and writers through the early 1950s.]

Mildred sympathizes with her father’s scroll of rallies and causes in the late 1940s including his draft of what became President Truman’s Point Four program. She describes a big peace convention - the “unhappy Waldorf meeting of 1949” at the Waldorf Astoria with its final event at Madison Square Garden.

She quotes from Shapley’s speech there listing Soviet faults and America’s - including racism (another Shapley theme). Inside, Madison Square Garden was packed with attendees as celebrities took turns onstage. Outside, Shapley and other organizers were “flanked by police and shouted at by an angry mob” stirred by accusations in the right-wing Hearst papers. This event “both lost and gained friends,” she writes mildly.

Nehru Drops By

Shapley made a month-long trip to India in January 1947 responding to a telegram “signed simply Nehru” asking that he “inspect our scientific laboratories.” The Rockefeller Foundation paid for Shapley’s travel. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru was arranging partition from Britain - just months away. Nehru was president of India’s science clubs; Shapley would speak wearing his hat as President of Science Clubs of America.

The University of Delhi had a special tent erected for the congress. Students overflowed to the aisles; faculty were in special section. Shapley tells Mildred:

“To my surprise, one-quarter of the tent, back of my platform, was blocked off. Funny business, I thought. Before I went on I asked the vice-chancellor’ and was told there were people back there.

“People? What people? Girls he said. So that was it - girls and boys not together - segregated. It sort of annoyed me….Consequently as I walked up toward the lectern, I looked over the barrier. Gosh what a sight! Hundreds of beautiful girls…all screeching happy to see the Galaxy Man! And in front…3,000 roaring males….” He greeted the students in front and those behind the screen on behalf of the 200,000 students in Science Clubs of America, of which he was president.

“ “… At every possible opportunity I made a reference to women in science… [T]he boys cheered and shouted.” Afterwards “the vice-chancellor came up to me, grasped my hand warmly, and said, ‘Dr. Shapley, you have done more for the liberation of women in education in India than anything else that has happened before.’””

“I want to see the astronomer, Shapley”

When Nehru visited America in 1949, he came to the Cambridge-Boston area. Harvard gave an official luncheon in his honor. “Oddly enough, my father was not invited, the reason being he was not a dean,” Mildred writes.

“But Nehru, when asked by President James B. Conant how he would like to spend the afternoon, said simply, ‘I want to see the astronomer, Shapley.’ Red tape was cut, and officials and motorcycle police escorted Nehru to the Observatory. In the retinue was his sister Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Indian Ambassador to the United States.

“He sat at my father’s round table in D-35, and in the library, saw [Donald] Menzel’s moving pictures of explosions on the Sun. They have remained good friends and exchanged letters over the years. At one time my father wrote to Nehru of a brilliant but unemployed Hindu student, Vainu Bappu, who had studied at the Harvard Observatory. Nehru promptly got him a job. Now Vainu Bappu is the top astronomer of India…”

STORY CONTINUES ⥥

Prime Minister Nehru and official party depart Building D after his surprise visit to Shapley at HCO. Photo by astronomer Margaret Harwood, Harwood Collection, US Naval Observatory.

III - COSMIC EVOLUTION

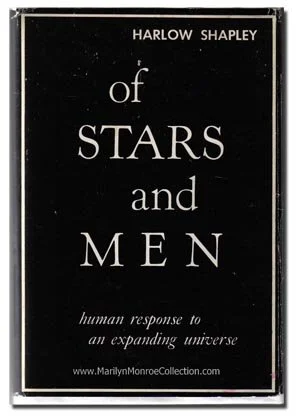

Cosmic Evolution, Of Stars and Men

The years 1940-1952 “were turbulent and intensely busy for him.” 191. Mildred alludes to wartime budget problems and staff shortages, but his last report as director, for 1952, showed a surplus. 200. In his 32 years HCO had grown from ten telescopes to thirty and personnel had tripled. The rules required that he retire as Director, but he could stay on as Paine Professor through 1956 to teach.

“You should get out, way out, and keep clear of the successor,” he says. 211. He exited the Director’s office and moved to C 36-38, the office of Annie J. Cannon who had died in 1941. The revolving desk was left out on the grass, but eventually rescued and shipped to Alan Shapley’s home in Boulder, Colorado. The Residence was torn down; the steep sledding hill facing Garden Street was smoothed. The south lawn which had been the scene of deck tennis and outdoor teas gave way to the construction of Building X.

Now as Paine Professor, Shapley devised and taught an undergraduate course on “cosmography.” Mildred writes it is “the field of study related to the cosmos as is geography to the Earth.”. More than a hundred students enrolled each term. He tells her “Every lecture was filled with by-play -- poetry. biology, paleontology, mixed with galaxies and the spacetime complex.” p. 213. He notes the essays by Radcliffe students were among the best. Story Continues ⥥

From hydrogen to Homo

The years 1952-53 brought a scientific breakthrough that clinched Shapley’s lifetime interest in evolution. When and how did the Universe begin? From about 1950 the leading model was the “big bang.” The first element created had been hydrogen. A central problem in astrophysics was how other heavier elements came about in stars, galaxies, novae, gas and dust and the early Earth. Shapley had always been fascinated by Earth’s geology and paleo life. But how on Earth did life arrive or arise?

In 1952 chemist Stanley Miller at the University of Chicago assembled inanimate compounds known on the early Earth, in a test chamber. When he bombarded the mixture with electricity to simulate lighting - lo! - amino acids formed - the bases of life! The Miller-Urey experiment published in 1953 clinched the link in the chain, from metal-rich elements swirling and coalescing to make a rocky planet Earth. In due course its atmosphere, ocean, land - and lightning - made life. This could happen anywhere that conditions were right, he noted.

“We have bridged at least provisionally, the gap between life and lifeless,” she writes channeling her father.

A Message in Anxious Times

Shapley preached evolution as the answer to unending cold war and imminent atomic war. Individuals can evolve; evidence of this is the progress of the human mind; we create poetry and science. Human societies have evolved and must evolve further to meet the tests of the future.

Amphibians, fish and insects have lasted millions of years compared to Homo’s recent arrival, But what of us? Would Homo survive even for 10,000 years?

We act like primitives fighting each other he said, arguing for peaceful cooperation. To avoid “extinction” we should mount an “assault on the unknown.”

To advance human knowledge, everybody should have a chance at education, Mildred notes his concern that much ‘human material’ is lost due to too little education and too much superstition.

Photo 12 Of Stars and Men, 1958 first edition,.HS’ copy.

These ideas came together in Shapley’s most influential book Of Stars and Men. It is just 157 pages and simply and eloquently written. When Mildred compiled her memoir in 1962 the book was in its fourth printing and translated into six foreign languages. She only summarizes and quotes a bit:

Our form of life arose on an unimportant planet on an unremarkable star in an ordinary arm of a galaxy that is just one of billions. Billions of galaxies are flying away faster and faster with distance.

“There should be nothing very humiliating about our material inconsequentiality. Are we debased by the greater speed of the sparrow, the larger size of the hippopotamus, the keener hearing of the dog, the finer detectors of odor possessed by insects?

“We can easily get adjusted to all of these evidences of inferiority and maintain a feeling of importance and well-being. We should also take the stars in our stride. We should adjust ourselves to the cosmic facts. It is a magnificent Universe in which to play a part, however humble.

Faith and John Hubley, successful film animators, approached him about creating an animated film of the book. Along with the delightful musical score by Bach, Vivaldi and others, Shapley’s voice narrates from his book’s text. When Mildred met the Hubleys at the 1961 Venice Film Festival, they said they hadn’t known any science but were inspired by his story and words.

Effective Religion

Mildred is a witness to Shapley’s faith that religion can be a force for social progress in the evolutionary scheme.

Shapley’s topic was Homo’s purpose in the universe - in relation to space, time, and life on other worlds. Inevitably he was asked about God. Shapley’s Round Table shows he revolved through religious debates of science and religion from the 1940s. Yet both her father and mother were “unchurched.”

His most productive venue was the Institute for Religion in the Age of Science. From 1954 it held a week-long summer meeting on Star Island off the New Hampshire coast. It drew 200 people of different faiths. Shapley was an avid member and president for some years.

“The general attitude of the conferences was that religious beliefs and teaching should increasingly recognize scientific thinking not as an enemy or threat to religion, but as an ally in the great enterprise of making human living ever more significant and comprehensible,” says Mildred.

Story Continues ⥥

Some Harlow Shapley Quotes on Religion

“Most astronomers are agnostics, not atheists - that presumes more than religion does. Science cannot accept blind faith. Ours is a perpetual inquiry; any firm acceptance of faith … brings inquiry to a halt.”

“Science is science; mythology isn’t.”

“Effective religions must now pay closer attention to reasonableness, and salute more diligently our expanding knowledge of a myriad-starred universe with its probably very rich spread of organic life.”

“When people asked him point blank … do you believe in god? - he answers, “Yes, certainly I believe in you and me and the atoms and the stars - we are all God. I spell it N-A-T-U-R-E.” My father admits that they go away rather baffled.”

STORY CONTINUES ⥥

Meeting the Pope Shapley admits to being humbled (unusual for him) upon meeting Pope Pius XII. The pope addressed the International Astronomical Union in Rome in 1952; the Shapleys were seated “protestingly” in the front row, he tells Mildred. Afterward the Pope stepped down from the dais to greet them. “He scared us, or at least me.” Shapley “stuttered;” the pope “passed on greeting the whole front row - in five languages!”

“Best service I can give in this decade”

He went on the road, lectured in some hundred colleges and universities. The American Association of Colleges was a sponsor. [The Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholars Program, which he devised with Kirtley Mather, arranged and supported this for two years, as did NSF and others.] Topics can be “spaceprobes, galaxies, origin of life, religion in the age of science, poetry and science” and occasionally “his life-long hobby of ants.”

He tells of his 1961 month in Australia. “I did the usual things expected of a tourist” such as “scratching the throat of a mother kangaroo” for photographers. He visited Mount Stromlo Observatory where Bok was now director. He visited the fine radio telescope. He met with students, gave talks and signed copies of Of Stars and Men.

Audience at a Shapley lecture in Australia, 1961. Photo: Harvard University Archives

For an appearance on the theme of suicide or survival, he pointed to the International Geophysical Year. He proposed an International Medical Year and International Cultural Exchange Year:

“We should all willingly ponder and work for such Homo-savers - for it is not in our stars, dear Brutus, but in ourselves that we may find salvation.”

“ Last week I did a job to a full house at Colombia University, and the night after at Brandeis University where I argued with faculty and students for three and a half hours… I may have a trip to Honolulu in September… and a California trip in August, and a short trip to Nantucket….. otherwise I am grounded among the pines and maples.”

Harlow Shapley during preparation of film Of Stars and Men ca 1960. Photo: John Hubley. ESVA Shapley, Harlow B1.

“I am … just now in deep Texas. In St. Paul I did ten talks in two days… 13,000 teachers heard me in Cleveland - 4 to 5 million (they say) heard and saw me on the Jack Paar Show. Maybe now they have had enough. Numerous requests for talks..…I am rather pooped.”

Mildred quotes from correspondence likely found on his desk in Sharon:

“’The impression he made on student minds will be a lifetime memory for them. His wit and brilliant satire created for us an impression of vitality and strength. Eight hundred individuals had an opportunity to hear, see, and be impressed by this great personality.’ President William Scarborough of Baker University, Baldwin City Kansas.

Buggy found in the Shapley’s barn in Sharon, N.H. was refurbished and enjoyed by five grandchildren. 1946. Shapley Collection

Pretend Horses

The barn had “ancient but well-preserved buggy… The Shapleys painted the body [with a] new coat of black, the wheel spokes turned pink, and the under springs became a bright yellow.

“Probably no horse after this gay transformation would be seen dead hitched to it - but we had willing two-legged horses - fathers and grandfather who would pull a load of gleeful children down the driveways.” - Mildred.

“My father’s comment on all this praising is, ‘I’m still fooling them.’”

“I guess praise and flattery are all right if you don’t inhale. But frankly, I’m a little tired of me…But if through my lecturing I have incident fresh new inquirers who will continue the assault on the unknown, all this speech-making may be justified…

Harlow and Martha Shapley at the doorway to their home in Sharon, N.H. ca. 1946. Shapley-Matthews Collection

“The revolutions of the planet are beginning to creep up on me. Let us enjoy the sunset over Mt. Monadnock, the asters and goldenrod in the meadow, and salute the Perseids that will shoot into our atmosphere tonight.”

IV - ABOUT THIS BOOK

The foregoing is longer than expected when I set out to relay closeups of “HS” at close range, especially to show how the life of the Residence interweaved with the lives of women and men at HCO in the Shapleys’ era. This became Part I.

In Part II I put stories from Shapley’s war and postwar phases that are unique in Shapley’s Round Table. I infilled the narrative to help today’s readers. Part III relays a bit that Mildred notes of Shapley’s pathbreaking role in the field of cosmic evolution.

Co-editors Here are those who this book in the public domain:

June L. Matthews, Co-editor is the first child of Mildred and Ralph Matthews. Born in 1939 she is the fluffy-headed blonde in family photos from Sharon in the 40s and early 50s. Her family heritage - drew her to astronomy and then physics. She earned her PhD in physics from tk in tk. In 1973 she took an appointment at MIT and rose to Professor of Physics. She was Director of the Laboratory for Nuclear Science from 2000 to 2006. Retirement in 2012 freed her take her mother’s manuscript off the proverbial shelf and organize publication.

June sketches her mother’s life and interests in an Afterword. She also describes their summers at Sharon, when the family drove from California on the break from Ralph Matthews’ teaching job. These were “magical times for my brothers Bruce and Melvin and me.“ There were “woods, trails, ants, gardens, wildflowers, construction and painting, conversation.” ”HS” and “MBS” loved baseball, so they listened to Red Sox games on the radio. “MBS, too, with her prodigious memory, could recite the batting averages of most of the players.” HS “planted a vegetable garden with some success, so they ate “what he called the ‘rabbit lettuce,’ because ‘the rabbit let us.’”

June presented her first scientific paper at the American Physical Society meeting in Washington in 1962. She invited her grandfather who was in town. HS attended and wrote to Mildred it was “excellently done!”

Mildred tackled some of Shapley’s scientific work in her manuscript. Astronomer Virginia Trimble of University of California Irvine, in her favorable review, urges readers to approach some of the science facts “with caution.” But Trimble admires the list of “his most substantial contributions in the field of astronomy” that Mildred asked her father to provide. (Se Quote below.)

Own J Gingerich Photo: https://socratesinthecity.com/guests/owen-gingerich/

Owen J. Gingerich deftly describes Shapley’s scientific contributions in an earlier essay “Shapley’s Impact” which is reprinted in this volume. Gingerich gave it to the IAU symposium on Globular Clusters, in honor of Harlow Shapley, published in 1988. One contribution from the Shapley-Ames galaxy survey was Shapley’s “forceful demonstration of the inhomogeneity of galaxy distributions.” See above The Universe at Breakfast.

Shapley presided “In a transitional age when a leader had to “marshal forces beyond a single person’s capacity.” “Did he not play a key role here as a catalyst for his colleagues’ discoveries? Surely the answer is yes.”

Besides organizing large-scale surveys with the instruments Harvard had, Shapley founded the graduate school; the first PhD was Cecilia Payne; he organized the Summer Schools - a model for intellectual sharing. His “enthusiastic internationalism” meant he took “delight” in hiring so many foreign staff.

Gingerich lays out Shapley’s “astonishingly wide reputation as a spokesman for astronomy.”

“I suspect that we all owe much in the public funding of science to this one man’s multi-faceted efforts -- through the press, through the pioneering radio talks on astronomy, through the Harvard books on astronomy, and through his ubiquitous appearances on the lecture circuit -- to arouse in an interested public a curiosity and fascination with topics astronomical.”

““I suspect that we all owe much in the public funding of science to this one man’s multi-faceted efforts … to arouse in an interested public a curiosity and fascination with topics astronomical.””

Thomas J Bogdan, Co-editor of Boulder, Colo, has a doctorate in physics from the University of Chicago. He was on the staff of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). He also was President of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR). He got to know the Shapleys visiting HS’ son Alan and his wife Kay at their Boulder home. Bogdan collaborated with June to digitize Mildred’s typescript. They deleted items published elsewhere. They kept Mildred’s original writing with only light edits.

Bogdan prepared Notes that give dramatis personae, key background, and a few corrections to the text Mildred wrote in the 1960s. The Notes have some of the wry humor as Mildred’s writing.

Notes Highlights

Martha Betz Shapley’s forbears emigrated from Germany in 1843 and settled in the Midwest, also Martha’s early life, education and marriage are documented. These will be described in my upcoming post in this series “Martha Shapley: Astronomer.”=

Albert Einstein did not attend the Great Debate between Shapley and Heber D. Curtis on April 26 1920 at the National Academy of Sciences. Einstein did attend another NAS meeting on April 25, 1921 where Shapley was present. Both Mildred and then Shapley in his 1969 light autobiography Through Rugged Ways to the Stars mixed them up.

Others in the story: Frank and Lillian Gilbreth; Harlow’s distinguished brother John Shapley and equally distinguished wife Fern Rusk Shapley; Martha Sharp of Ken Burns’ “Sharp’s War;” Virginia Nail; Dorritt Hoffleit; Cecilia Payne; Donald Menzel; “Mr. Magoo.”

The Observatory Philharmonic Orchestra founded by Frances Woodworth Wright had its first season in 1949. The first program lists players; the violinist concertmaster was Cecilia Payne-Gaposhkin. The first number was the debut of “George” a double bass made from plywood and two-by-fours by student William Liller.

In one Note Bogdan confirms that, unknown to Shapley, the FBI bugged him from 1946 for many years.

The revolving desk “was summarily removed and tossed on a scrap heap” when Menzel succeeded Shapley as Director. “James G. Baker rescued it from its destruction.” It was fixed for a room in Alan and Kay Shapley’s home in Boulder, Colo. When they moved in 1995 it was still Harvard’s property and transported back to Cambridge. It now resides in the home of Harvard historian Sara J. Schechner.

Of equal or greater interest to Shapley fans is the “solution to the formicine mystery” - the classic HS riddle: How could two ants he had pickled in vodka at Stalin’s banquet and brought home, become just one in the vial, tucked in his revolving shelves in Cambridge? (See above Stalin’s Ants, Poulkova Ruin).

June asked the renowned Harvard naturalist and entomologist E.O. Wilson to provide a comment on Shapley’s contributions to myrmecology for this volume. Wilson wrote an ample comment, excerpted here as a final close-up.

Story Continues ⥥

Of Ants and the Man

From 1951 at Harvard, Wilson worked toward his PhD and then was elected to the Society of Fellows. He had many conversations with Shapley and learned that he collected specimens as he traveled around the world. Shapley told him of the two ants from the Kremlin he had IDd as common Lasius niger. Wilson said he was studying this species and would love a locality record - from Stalin’s residence, no less. Wilson borrowed the vial, took one ant and added it to the Harvard collection. “I never got around to returning the loan.”

Another E.O. Wilson memory of Harlow Shapley suggests the goodwill toward <this fascinating visitor,> a touch that would have stayed buried if Shapley’s Round Table had not dug it out.

Wilson recalls that years later at the Harvard Faculty Club Shapley tapped the younger scientist on the shoulder. He told Wilson: “I’ve just told [President] Pusey that you are the most important assistant professor at Harvard.”

Wilson wrote, “I’ve never received a compliment that meant more.”

STORY CONTINUES ⥥

E.O. Wilson: Left As young professor in the 1950s. Right: Displaying specimens. Credits: Harvard NARA and Takieng. Montage by the author.

GALLERY - MILDRED SHAPLEY MATTHEWS

Mildred with Dave Jurasevich and Don Nicholson in Pasadena in 2013. Don’s father “Seth Nicholson was my father’s closest friend at Mount Wilson.” Photo: Tom Meneghini

Mildred in 1993 upon receipt of the Harold Masursky Award of the American Astronomical Society. Photo: University of Arizona

While looking for satellites of Jupiter in 1916, Shapley discovered a new asteroid. He and Nicholson agreed to name it Mildred. Above orbital view of Asteroid Mildred 878. Image: JPL

Mildred with “little” brother Lloyd and her daughter June Matthews at 2012 Nobel ball. Photo Nobel Foundation. USE MY CROP

Shapley’s Round Table: A Memoir by the Astronomer’s Daughter

Mildred Shapley Matthews

June L. Matthews and Thomas J. Bogdan, Editors,

295 pages, BookBaby, 2021 $20.00

““This book makes me feel as if I had known Harlow Shapley as a colleague and a friend.””

The author thanks first aunt Mildred for writing this memoir and then June Matthews for advancing its publication. Thanks go to Tom Bogdan for helping with the book and for the full Harlow Shapley Bibliography on this website. Many at Harvard have helped me: Owen Gingerich, Maria McEachern of the Wolbach Library, Tom Fine and Harvard University Archives. Special thanks to Sophia Ojha, site designer and cataloger of project images. - D.S. February 2023