Drawing on one of the most famous debates in scientific history, Deborah Shapley poses the question whether head-to-head conflict is a model that benefits science. She offers a wider version of the story of her grandfather Harlow Shapley’s loss after 1920 debate with Heber Curtis, at which Shapley argued “island universes” were located inside our Milky Way Galaxy. But in the 1920s when Edwin Hubble sent him evidence these “nebulae” were way beyond our galaxy, Shapley pivoted to the view he had opposed. For decades afterward, Shapley pushed scientific work on galaxy distribution and spread public knowledge of this unfolding universe.

Shapley’s work with other astronomers during this revolutionary time was more collaborative than is usually told. Deborah suggests that telling the story of the Great Debate as head-to-head conflict is not the best way to present this famous event.

Below are the full slides and a summary of Deborah’s lecture to the National Capital Astronomers meeting on December 9, 2023. Slides referenced in the text are by the pound sign #. Use the NCA icon to hop to video & audio of the lecture on the NCA website and learn more about NCA.

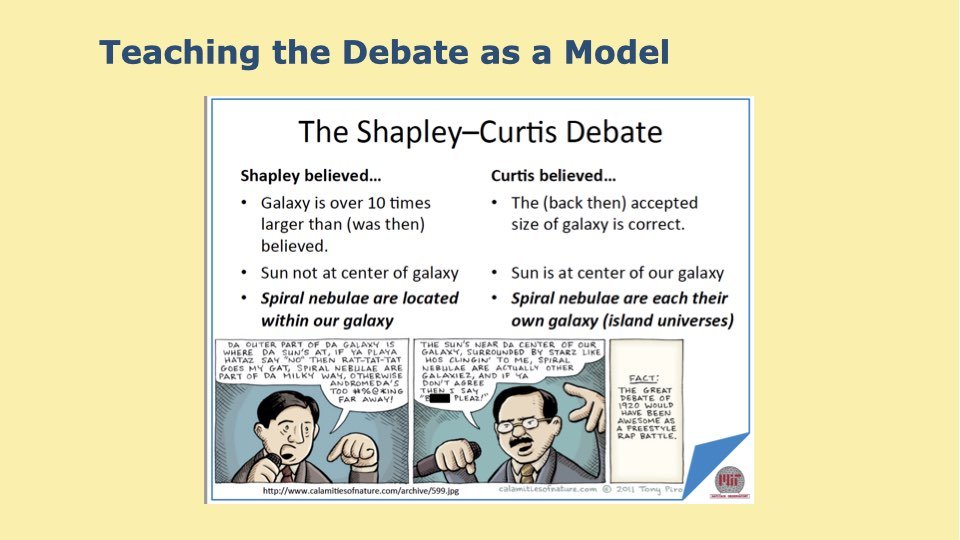

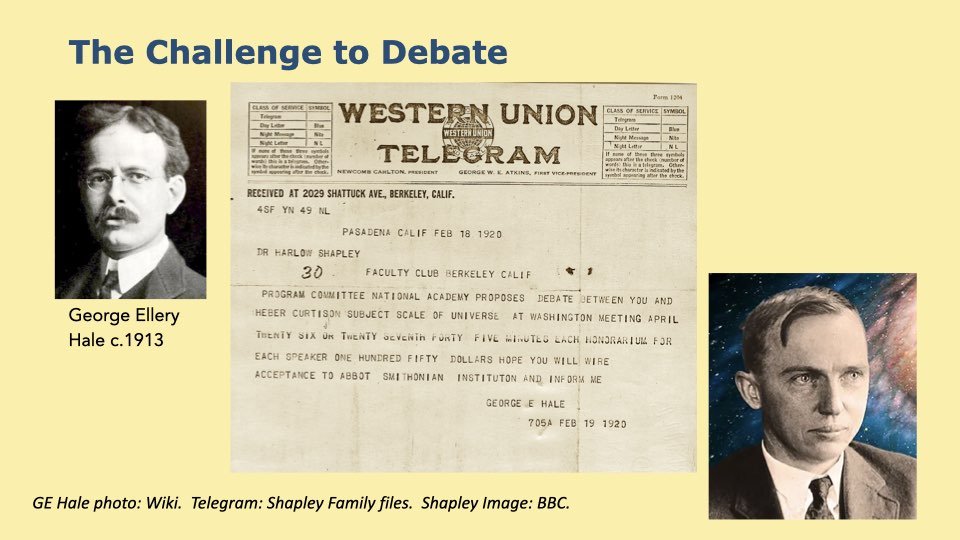

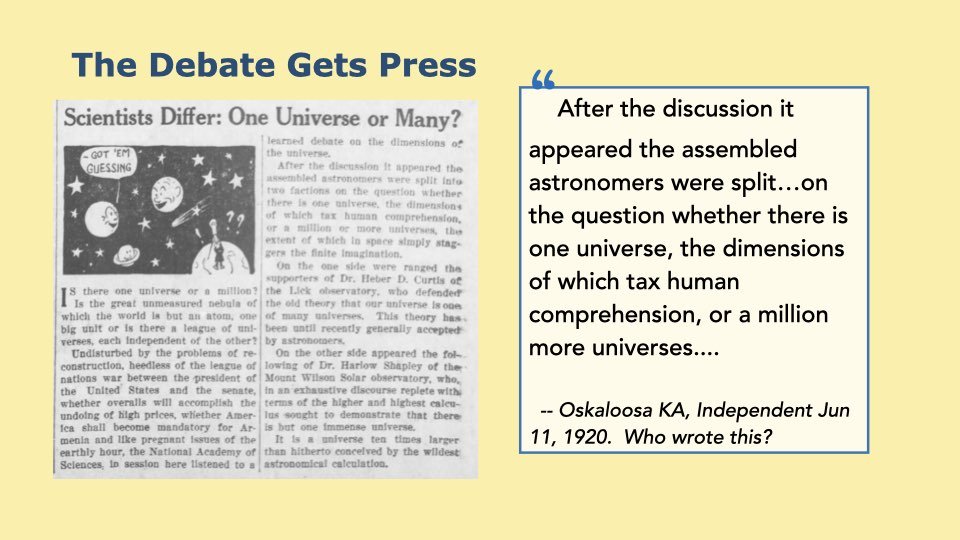

“The Scale of the Universe” was the title of a debate between Harlow Shapley and Heber D. Curtis on April 26, 1920. They spoke before members of the National Academy of Sciences in Washington DC on the stage now called the Smithsonian Baird Auditorium. In later years the event gained fame as the Great Debate. It is widely studied and taught. See #3, #35.

Shapley, the 34-year-old prodigy at Mount Wilson Observatory, described his startling new model of our Milky Way galaxy, which was believed to be the universe. In 1918 Shapley had mapped it as a huge disk with a dense center 60,000 light-years away from our sun. The senior 48-year-old Curtis defended the long-accepted view that the Galaxy was bun-shaped and 10,000 CK light-years across. Curtis kept our solar system at its center as everyone believed since Copernicus in 1543.

The two men disagreed about “island universes” - the odd, fuzzy nebulae that no telescope at the time could see clearly. Shapley maintained they were within his Big Galaxy. Curtis, echoing his fellow astronomers at the Lick Observatory, said they were way beyond, in other words, that our universe has a plurality of worlds of some undefined kind. The issue was not settled until January 1, 1925 with Edwin Hubble announced his discovery of “spiral nebulae” light years beyond Shapley’s galaxy. Hubble’s proof revealed the true shape of the universe.

Why it matters. “Future historians will always want to learn about the time that humanity learned there was a whole universe of galaxies out there, and so they will always be drawn to this focal point of this disagreement: the Curtis-Shapley debate,” wrote R.J. Nemiroff and J. T. Bonnell in a very clear “Lesson Plan for Undergraduates” in 1995.

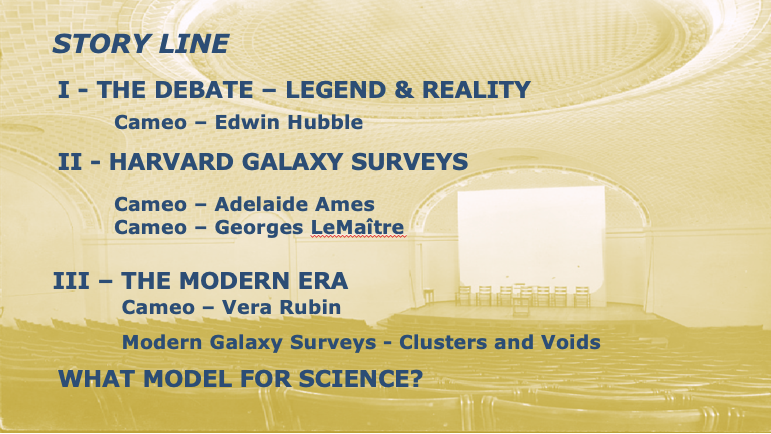

I THE DEBATE - LEGEND & REALITY

Debates in science are often presented as head-to-head combat with clear winners and losers. In the standard story of the 1920 debate, Shapley wandered among topics - introductory astronomy and a light meter he’d invented. He defended his model of a Big Galaxy and his use of Cepheid variable stars as his basic yardstick for measuring long distances across space.

One way students absorb ‘lessons’ about science is through caricatures and cartoons. See #4, #5.

Curtis gave a polished lecture with slides. Afterward, he told others he had won. It is said that most people at the event thought so too. Though Shapley did not admit he lost onstage, he was privately self-critical of his performance.

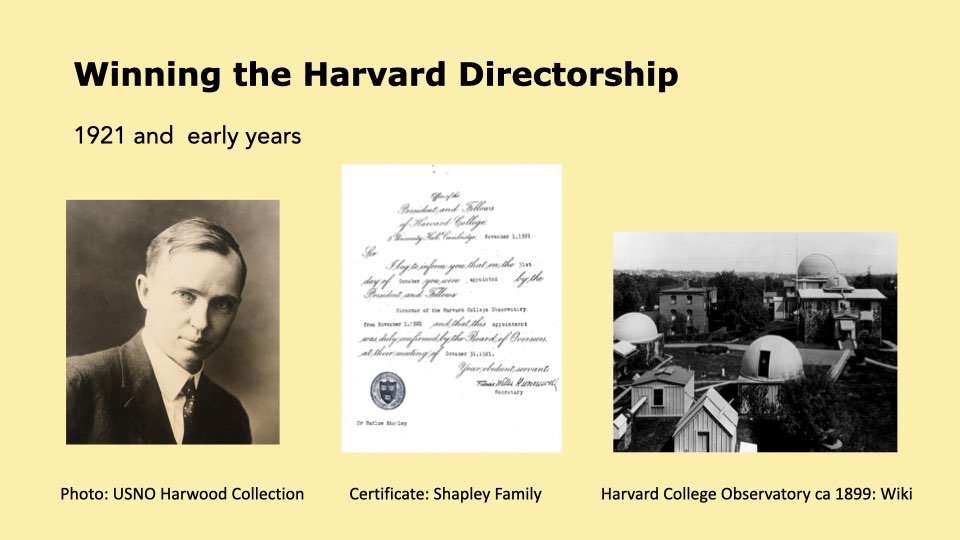

They exchanged written texts which were published in May 1920. These were used as the record until historian Michael Hoskin found the transcripts in 1976. Hoskin concluded that Shapley’s presentation mostly aimed to impress some Harvard men in the audience who could advance his candidacy for the vacant post of Director of the Harvard College Observatory.

The core of scientific inquiry includes doubt in Nemiroff and Bonnell’s description. See #6.

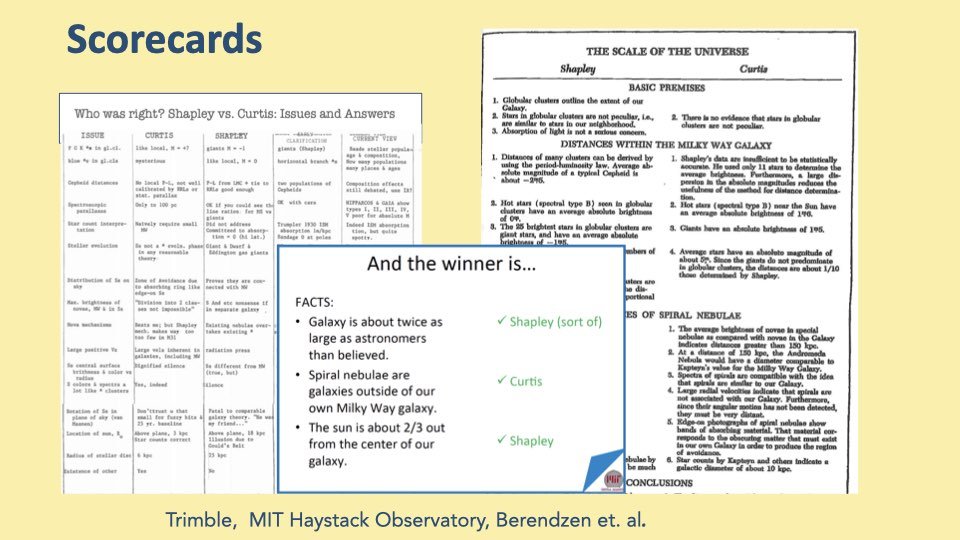

Three scorecards by scholars who went through the many cross-cutting issues are on #9. My audience of astronomers tonight likely knows the issues. On content, they show Shapley almost a draw. See #35 for literature citations.

Applying my journalist’s and layperson’s perspective, I reviewed Shapley’s public statements and press coverage in 1920-21. He was, of course, right on the Galaxy is much bigger than Curtis et. al. assumed, on its dense center and the sun’s eccentric location. On the island universes he took different positions at different times.

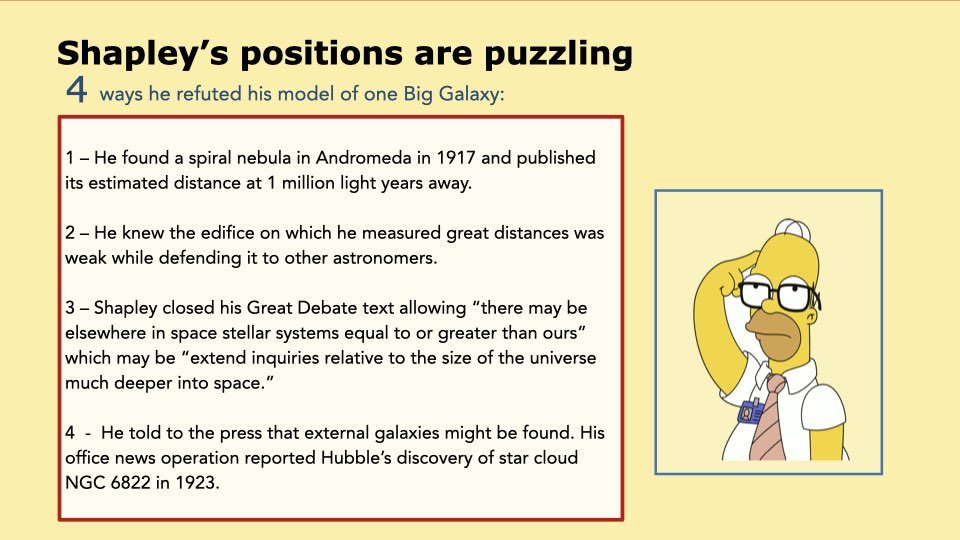

Shapley’s positions seem puzzling until we consider Nemiroff and Bonnell’s description of debate reality. On #13 while Homer Simpson scratches his head, I list four reasons that, as a scientist, Shapley knew his position was weak and the spiral nebulae could be outside his Big Galaxy after all.

If Homer Simpson can be puzzled, scientists can be as well! See #13

Yet the standard narrative, including by Hoskin and Owen Gingerich, have him losing on other issues — ironically just when his Galaxy model was winning acceptance. He was bold in seeking the Harvard job - such as planting stories about his great work in the papers. But he won the job; he moved to the observatory, ostensibly in a temporary role; he was made Director one day before his 36th birthday.

A graver loss is rightly noted. In 1917 at Mount Wilson, Shapley had found a spiral novae he calculated was one million light-years away! By not following up he missed the biggest coup. We have not the Shapley telescope but the Hubble!

Hubble’s measurements showed that “island universes” were far from our Galaxy, showing Shapley’s earlier claim to be wrong. See #12

Hubble wins on island universes

Hubble used Shapley’s application of the P-L Law to measure distances to the Cepheids he was finding with the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson. See #12. (His use of Shapley’s toolkit was not always acknowledged.)

They corresponded closely. Shapley had access to earlier plates and Hubble had new light curves.

Hubble finally announced in January 1, 1925 paper that he had detected Cepheids in the nebulae M31 and M 33. He computed that each was 285,000 kpc away, placing them beyond even Shapley’s Big Galaxy. (R Smith 117. Feb 19 1923 Letter is 112-117.)

“Shapley, in response to the growing body of evidence, at last saw the scientific handwriting on the wall. He cried uncle, acquiescing speedily and graciously….Once proven wrong, the Harvard Observatory Director didn’t look back and quickly adjusted to the new cosmic landscape, becoming its most boisterous promoter. ”

“Wrong” or “right” on the size of our galaxy? The debate about distances to the nebulae did not end with Hubble’s paper; he had only proved that some were unquestionably beyond. The new era continued intense collaborations and rivalries.

Another way Shapley was “wrong” was on the size of his (our) Big Galaxy. In Gingerich’s telling, another “nail in the coffin” arrived in 1930, when Robert Trumpler published evidence that parts of our galaxy occluded by interstellar dust. As a result, objects seen across the central region looked more distant than they were. This work didn’t make Shapley’s model ‘wrong’ so much as scaled the size back somewhat - and cleared out a problem that had dogged everyone’s measurements. The reduced diameter left it closer to Shapley’s than the old small model. (Today’s value is about 30 kiloparsecs or about 100,000 light-years.)

II. Harvard Galaxy Surveys

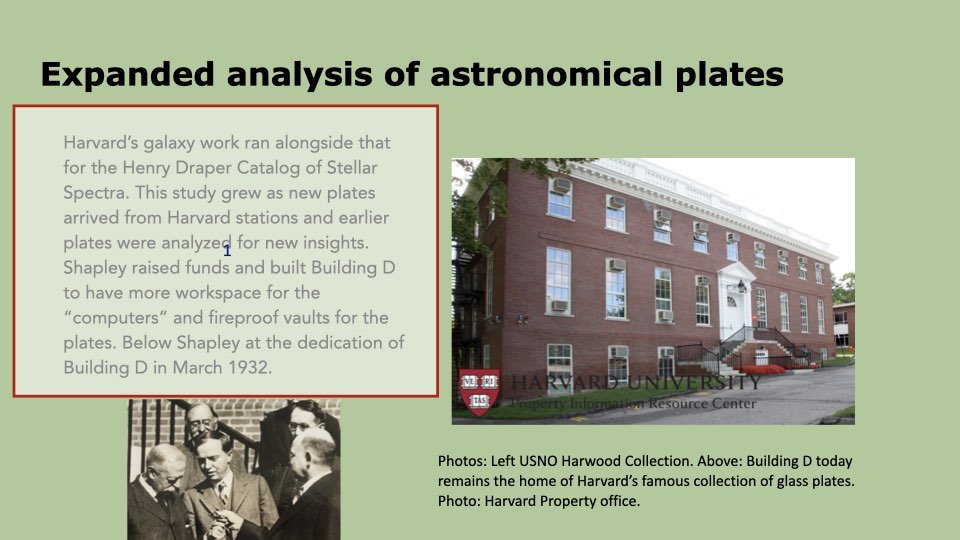

On November 1, 1921 Shapley became Director of Harvard College Observatory. It held the largest astronomy data collection in the world, and unparalleled expertise in stellar comparison and analysis. His plan was to take Harvard Observatory into research and publication and update its facilities for gathering data from the southern and northern sky. In the twenties, he moved the Peru station to a better site in South Africa and got funds for a 60-inch telescope there.

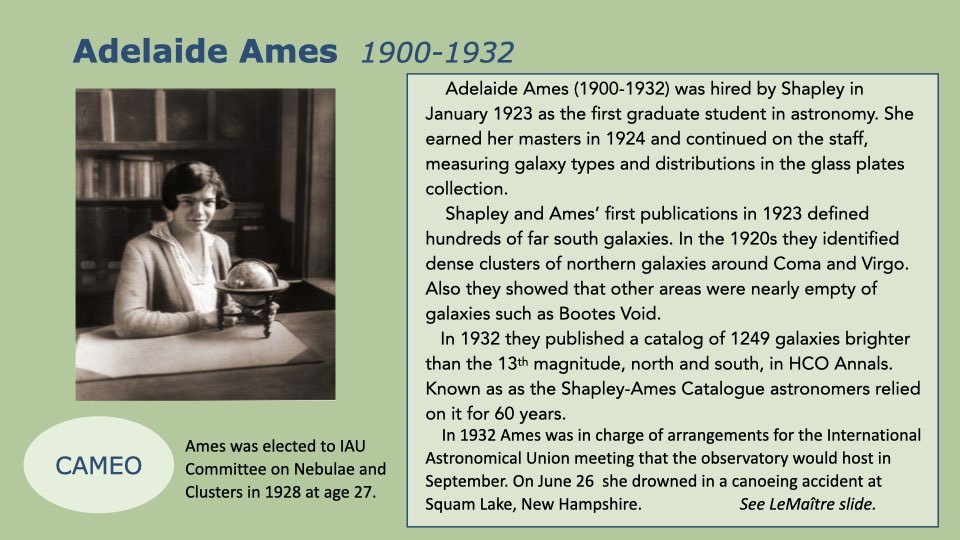

Adelaide Ames analyzed and mapped galaxies at Harvard through the 1920s. She was elected to the IAU Committee on Nebulae in 1928. Tragically, she drowned in a canoeing accident June 26, 1932. See #15-17.

Adelaide Ames was the observatory’s first graduate student, hired by Shapley in January 1923. She got a master’s in astronomy in 1924 and continued on staff. She specialized in defining the plate records of the brightest spiral nebulae.

Shapley preferred to call them “galaxies” and the term caught on. Hubble and his colleagues kept the term “extragalactic nebulae” - another sign of the division between East and West Coast astronomers.

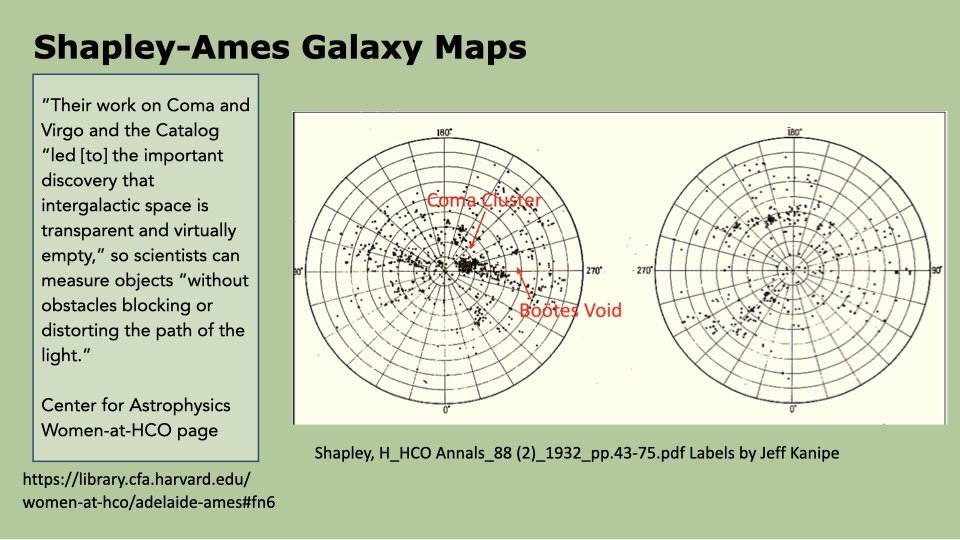

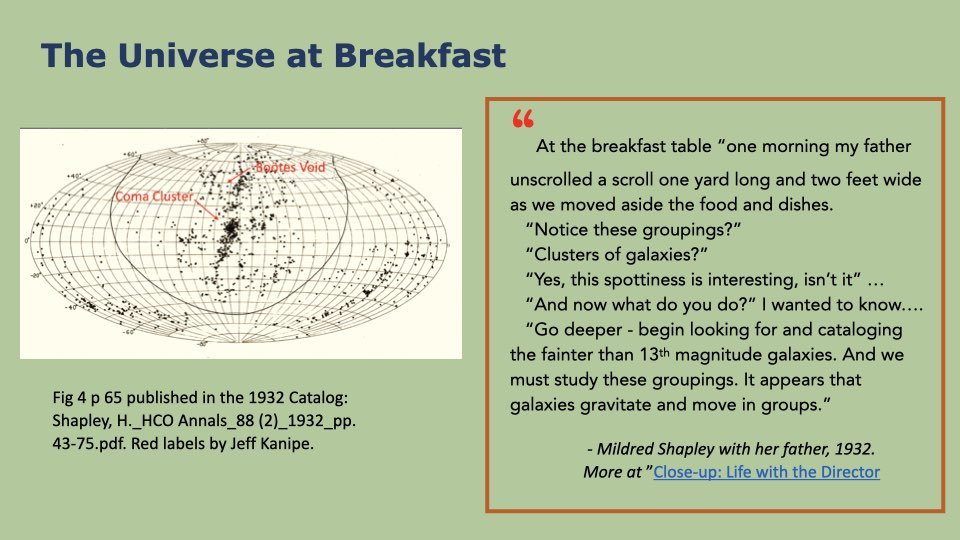

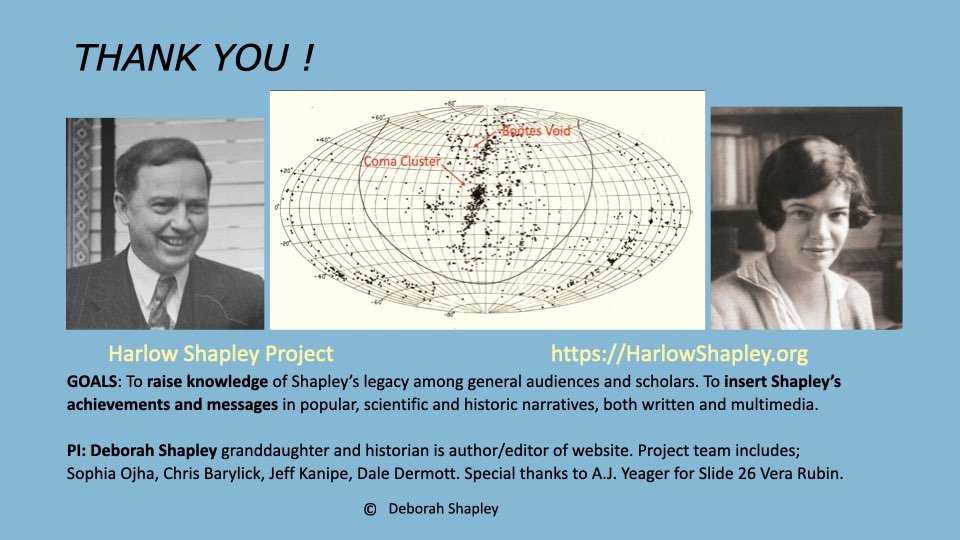

Shapley and Ames published many papers in 1923-31 on the distribution of the “spiral nebulae” with magnitudes and distances and CK. Some were the farthest ever seen. They found and plotted dense clusters in the constellations Coma and Virgo. They found that other areas were nearly empty of bright galaxies, such as that known as Boötes Void. Their discovery of the transparency of intergalactic space meant astronomers could compute distances there.

The galaxies sorted into a few distinct shapes; so how they evolved was another puzzle. To order them for standard reference in their catalog, Shapley discarded his own classification scheme for Hubble’s system, which was a revision of his earlier one.

Shapley and Ames found the wildly uneven distribution of bright galaxies - a departure from the rule of a uniform universe that astronomers and physicists assumed. Some gathered in clusters, some seemed to have more clusters piled on. They appeared to move gravitationally in relation to one other.

Shapley, H._HCO Annals_88 (2)_1932_pp. 43-75. Red labels by Jeff Kanipe. See #18-#20.

The result was a catalog of 1249 “external galaxies” brighter than the 13th magnitude - all that could be detected from the plates of the northern and southern skies. The Shapley-Ames Survey was published in 1932. One of their actual maps is above; we marked a few famous locations in red. Also see #18-#20.

Ames’ contribution is impressive! She has 32 entries in NASA ADS; nearly all papers are with Shapley. Many are from 1927-29 and about Coma and Virgo.

In the 1920s, while Ames and Shapley plotted galaxies, another character entered - or may have entered - the story. Georges LeMaître a Belgian Catholic priest had trained under Arthur Eddington at Cambridge, UK; LeMaître came to Cambridge, Mass. in 1925 to work for a PhD in physics from MIT.

LeMaître’s presence at HCO was mentioned briefly by Shapley in his Director’s Report, the 80th covering the 1925-26 academic year. LeMaître is “studying the pulsation theory of variable Cepheid stars” as a “Fellow of the C.R.B. Educational Foundation.”

LeMaître received little notice for having modeled in the expansion of the universe in 1920s, which he published in 1927. In 2018, the IAU voted to rename Hubble’s Law, the cornerstone definition of the expansion, the Hubble-LeMaître Law. ScienceInsider 10-28-18.

In 1927 back in Belgium, LeMaître published his theory that the expansion started from a “super atom”, later called the “primeval atom.” As the new universe pushed outward, an uneven contraction might have created large structures. It seems likely that when visiting Harvard in 1925-27, the quiet, brilliant priest pored over the maps showing clusters and voids. that Ames and Shapley were creating.

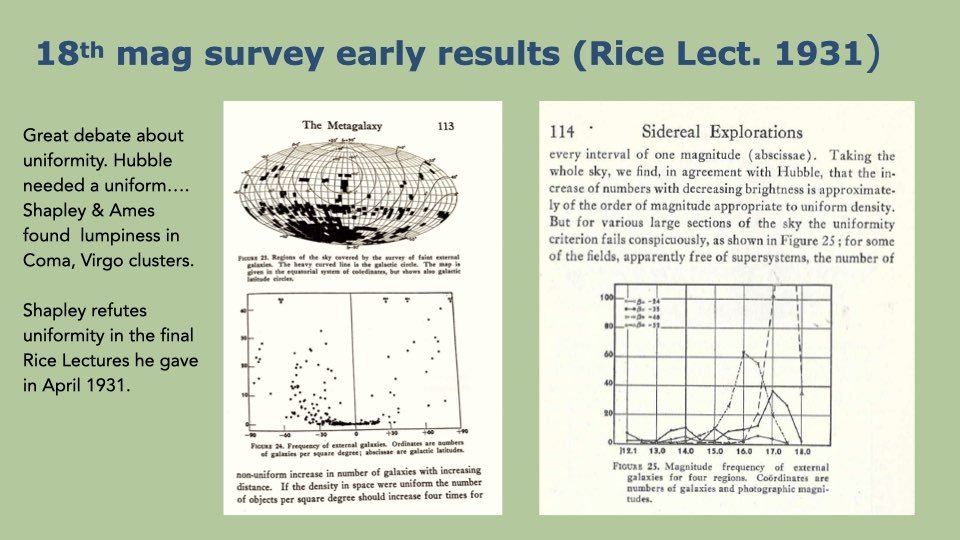

Another battle of titans Shapley launched an extension survey of fainter galaxies out to the 18th magnitude detectable. Search and analysis continued on existing plates and northern plates from the new Oak Ridge station and of the southern sky from Boyden Station in South Africa.

“Especially the 18 magnitude survey began to show the irregularities of galaxy distribution,” writes Owen Gingerich. By then Hubble was computing the rates of expansion through space. He was sure that the overall mass would even out because of the principle of homogeneity that astronomers and physicists held dear. But the Harvard cluster data showed different regions are not uniform out to the distance measured so far.

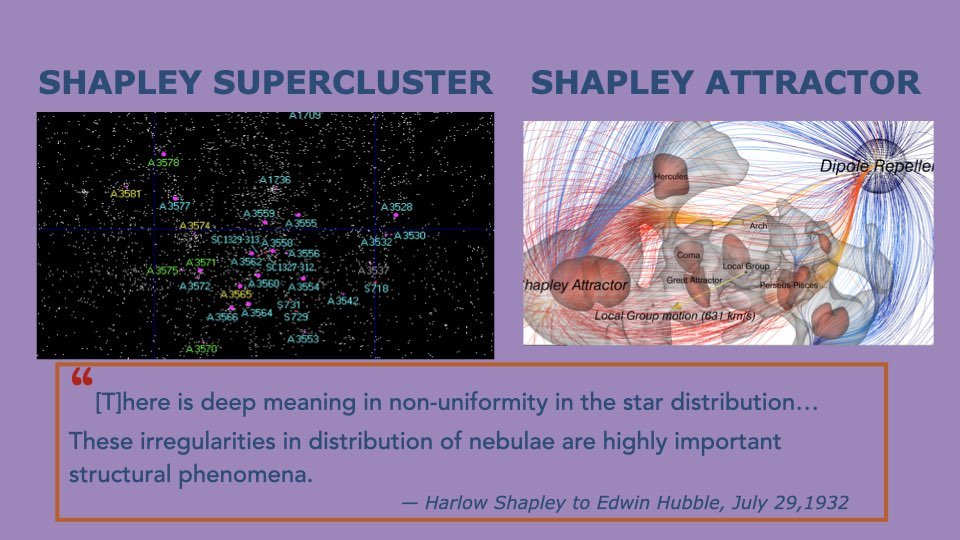

“You may think I emphasize the irregularity too much. But there is deep meaning in non-uniformity in the star distribution…These irregularities in distribution of nebulae are highly important structural phenomena.”

III The Modern Era

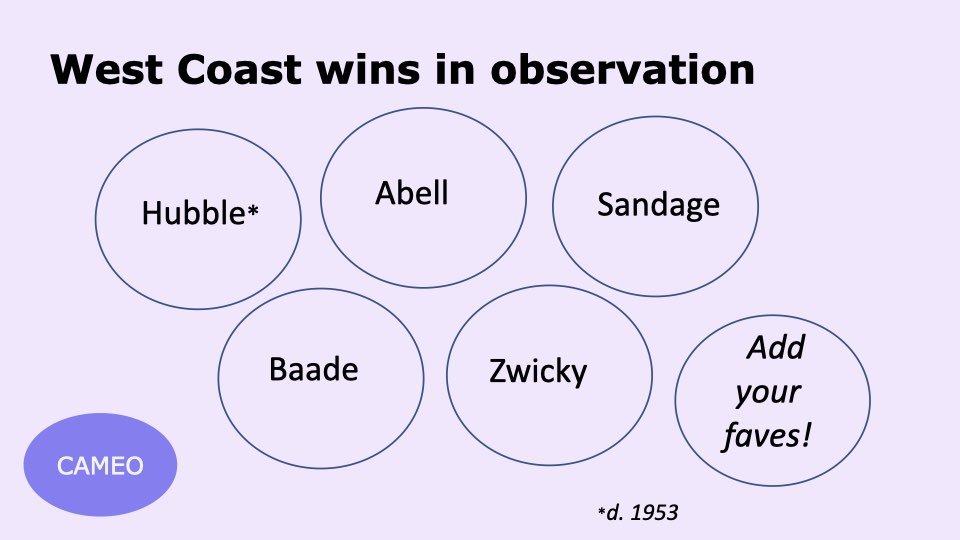

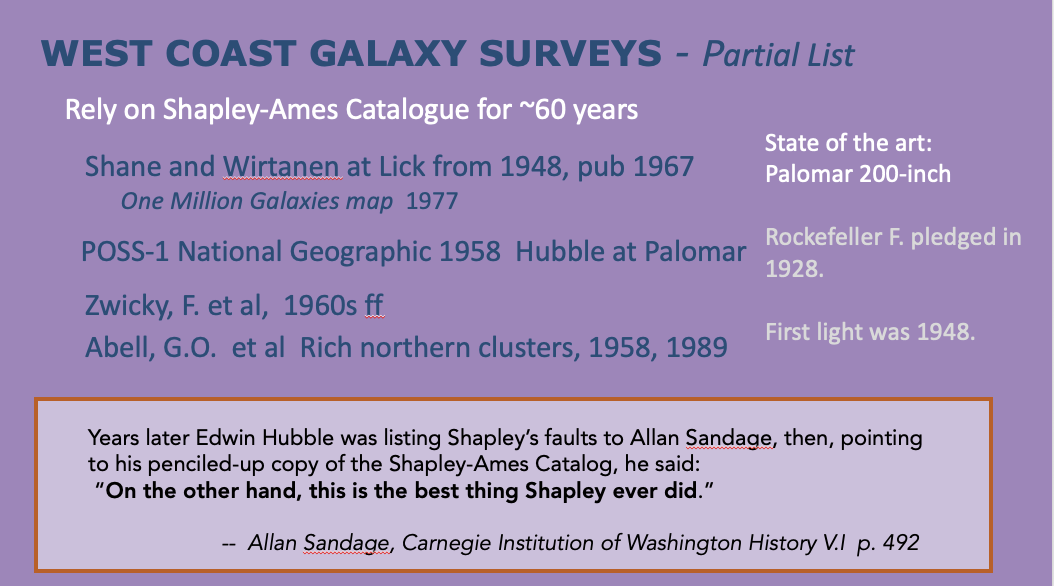

Harvard observatory was “locked out” of the forefront of observation when California won funding for the next generation, the 200-inch telescope at Palomar and 20-inch astrograph at Lick. These could penetrate farther over limited areas - and discovered new properties in the nebulae.

Harvard kept its advantage in large-scale surveys, especially of the southern sky. To intake data for this survey and for the Henry Draper Extension Catalog of stellar spectra, Shapley kept the unique South Africa telescopes going during World War II.

A very brief list of West Coast galaxy surveys suggests some of the uses made of powerful new tools. In only a few decades the extragalactic spiral nebulae - whose existence Shapley had disputed - had become a possibly infinite population of new worlds at the cutting edge of research.

The Harvard 1932 catalog of the brightest galaxies remained the foundation.

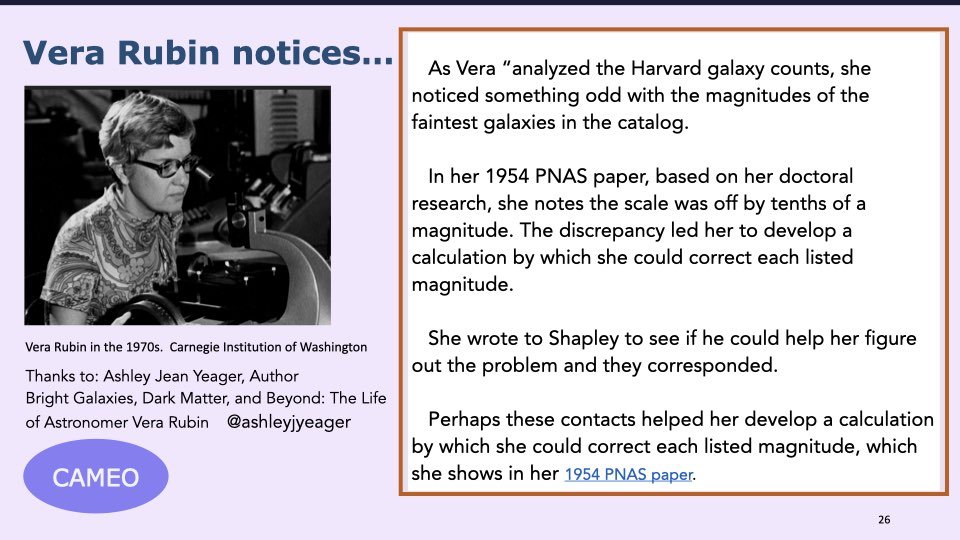

Astronomer Vera Rubin studied the Shapley-Ames catalog closely in 1952-53 and noticed the magnitudes of faint galaxies seems “off.” See #25

Secret clue in the catalog

The Shapley-Ames catalog held a clue to another leap in astronomy for someone who looked very carefully.

Vera Rubin noticed the magnitudes of the faintest galaxies, were off by tenths of a magnitude. She wrote to Shapley to ask about it. Could their brightness be affected by something else? Rubin and Kent Ford’s confirmation of dark matter followed in 1978-80. In 1933 Fritz Zwicky at Caltech concluded the Coma cluster had hidden nonluminous matter he called “dunkle Materie.”

Meanwhile, what were these clusters doing? The catalog showed independent concentrations of galaxies in motion. Were those in the Local Group near our big galaxy drawn by it? By other forces? Surveys farther out showed yet more clusters, also moving. Were these distributions by chance?

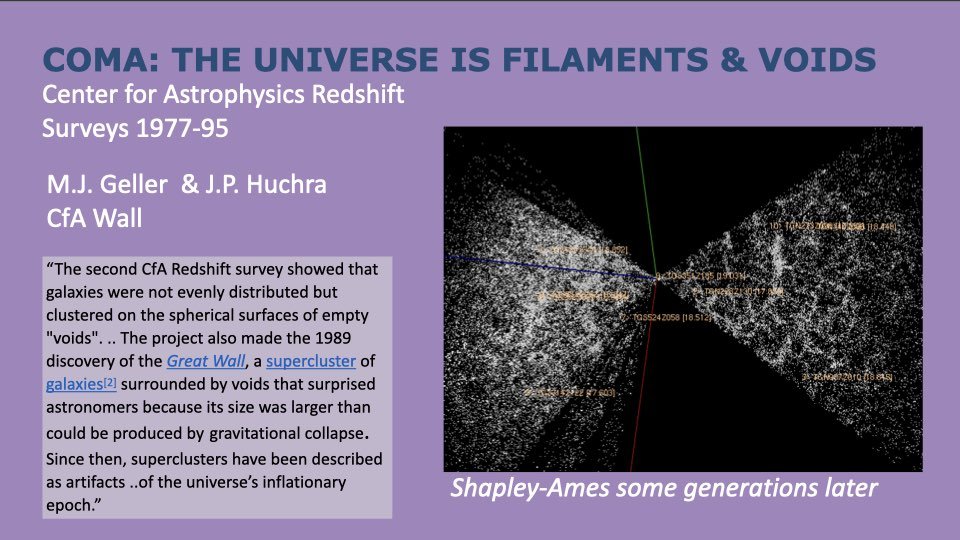

The large-scale structure was investigated by many. G. de Vaucouleur is credited with the term “supercluster,” though the pileups in two and three dimensions had been clear. In 1977-82 the Center for Astrophysics (formerly Harvard Observatory) launched the first sky survey in redshift. This and a second, CfA2 from 1985-1995 mapped the galaxies in three dimensions as they moved. These beautiful images showed clusters strung together by filaments and divided by spherical voids. The most spectacular discovery was of the “Great Wall” by John Huchra and Margaret Geller, published in 1989.

“Years later Edwin Hubble was listing Shapley’s faults to Allan Sandage. Then, pointing to his penciled-up copy of the Shapley-Ames Catalog, he said:

“On the other hand, this is the best thing Shapley ever did.” ”

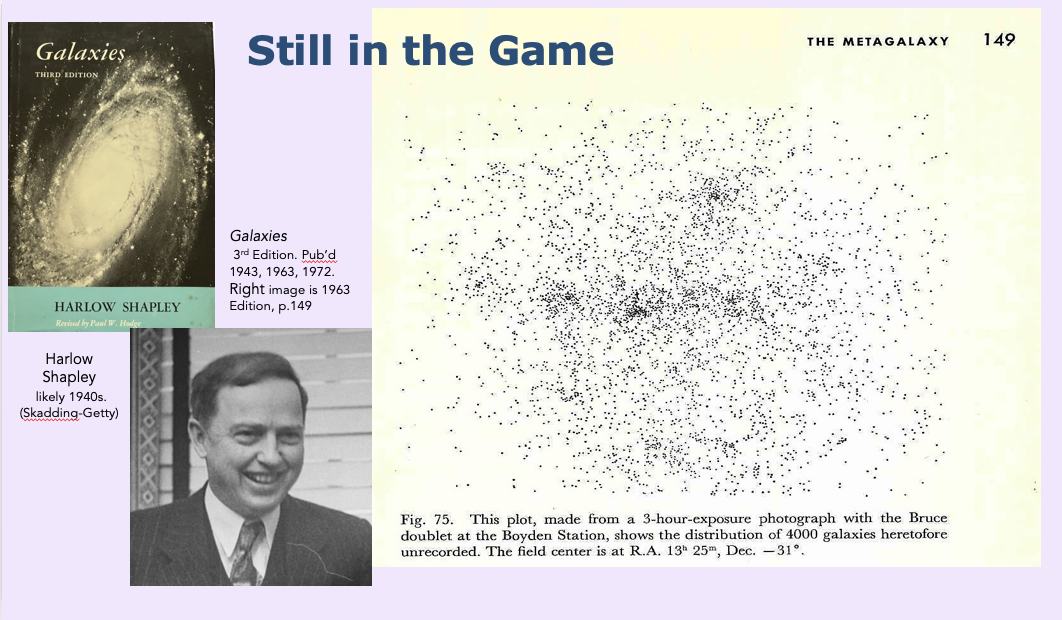

Harlow Shapley in about the 1940s. See #30. Photo: Skadding-Getty.

Shapley kept on seeking to define “the scale of the universe.” His articles, lectures and books on astronomy posed the problem: What was the distribution of galaxies even as they seemed to recede indefinitely? Did the overall density gradient change? If the mass got denser, there could be an edge, a closed universe. But as he would say So far “no bottom.” Astronomers must probe farther out systematically to solve the grand question.

Shapley’s influential primer Galaxies was published in 1943, 1963 and 1972. See #30.

His West Coast critics fumed through the years about this fault, including his popularity and wit. Elsewhere Shapley was hailed as the modern Copernicus who created the Harvard astronomy graduate program, with alumni now leaders in the field. He stood up to the Right on research freedom, got the “S” UNESCO, and helped shape the National Science Foundation. He was in constant demand as a lecturer and widely-read author who endlessly promoted science. Examples are A Treasury of Science (1943, 1954, 1958, 1963, 1965, Book-of-the-Month-Club) and Galaxies (1943, 1963 and 1972). More on his public role in the 1950s and 1960s is in on this blog in Part III of Shapley’s Legacies after Mount Wilson.

WHAT MODEL FOR SCIENCE? Tonight’s talk is only a sketch. I merely tried to connect the story lines from a wide range of material which hundreds of specialists know far better than I!

To me it seems clear that Shapley winced at his poor showing onstage at the 1920 debate, so he tried to pick up his public speaking as he matured! Also at the time of the debate he knew his position on the island universes was weak. So when Hubble shared hard evidence, Shapley cried uncle and embraced the new vision. The exciting new possibilities spurred him on. As HCO Director he devoted much of his scientific work and the talents of a talented young woman astronomer to study the distributions of island universes/spiral nebulae/galaxies. Thanks to him we use the simpler term “galaxies.”

I’ve been told that West and East Coast astronomy has had long-running conflicts, and the opposite personalities of Shapley and Hubble played a role. Think about it: how could our galactic knowledge have advanced better?

Is head-to-head conflict the best way to showcase science? Maybe we can structure debates more collaboratively. We can also teach students and aspiring scientists that, after you lose, you can effect good science!

“ Today what we need are more of these debates. This would allow the community of scientists to share with the public the turbulent paths that lead to scientific discovery - paths that reveal science, not at its worst, but at its best. ”

NATIONAL CAPITAL ASTRONOMERS

Deborah thanks the NCA hosts and members who attended. She thanks everyone for the lively debate (!) afterwards and her great project team. See #34.

Deborah’s talk was “enjoyable and informative to watch. John Hornstein President of NCA said. “It conveyed a lot of information about the science and the personalities, and enriched our picture of that period.”

Recording of the Presentation

Deborah video starts at 18:25 and ends at 57:58 when discussion began.

Deborah audio only here.

Note: Some slides on this blog post are tidied up from those shown Dec 9.

National Capital Astronomers

You do not have to be an astronomer or astronomy major to join! One of the most inclusive astronomy clubs in the US!

Click the button below to view more videos from NCA meetings.

CapitalAstronomers.org